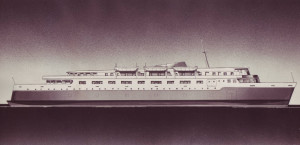

Black Ball Ferry Chinook was last word in comfort

A tribute to “the Queen Elizabeth of the inland seas”

It’s hard to believe, today, that in 1946-47, Victorians were as interested in Washington’s newest car ferry as the citizens of Seattle. That’s when the M.V. Chinook was said to be the last word in Pacific Northwest commuter comfort and elegance.

So proud of their new-born flagship were the directors of Puget Sound Navigation Co., the parent firm of Black Ball Transport, that they touted her as “the Queen Elizabeth of the inland seas”.

The launching of the $2.5 million lady at Seattle’s Todd Shipyards, April 22, 1947, was a gala event. Victoria was represented by Mayor Percy George and members of the chamber of commerce along with officials of Ports Angeles and Townsend. Capt. Alex Peabody addressed the assemblage on behalf of the PSNC:

“Permit me to say a few words about the ship which brings us here today. You can be assured that our directors and officers, together with the officers and technicians of the Todd Shipyards Corp., have spent a great deal of time in our endeavors to produce a vessel that would be more than adequate for the trade for which she is intended… [The naval architect firm of Gibbs and Cox, New York] have come forward with a vessel which we hope will meet with your unqualified approval…”

Capt. Peabody said she was 318 feet in length, 62 ½ feet in the beam with a draft of 13 feet. Her four diesel engines were installed well below her spacious main deck, which enabled a cargo capacity of 100 vehicles. Her twin propellers and rudders gave Chinook maximum manoeuverability and a normal cruising speed of 18 knots.

Her spacious lounges and covered promenade decks could comfortably accommodate almost 1000 passengers

Her stateroom facilities on three decks included two bridal suites, could sleep 200 in “deluxe, super-deluxe and cabin-type rooms all of which are quipped with ‘combolet’ lavatories and air conditioning”.

Another innovation was that all rooms were furnished with twin beds. Dining accommodation for as many as 120 persons at a time was situated aft, to give “a complete panorama of Puget Sound scenery”.

On June 20, 1947, Todd Shipyards delivered the shining new Chinook to her owners. Six days later, she sailed on her maiden run, linking Seattle with the northern Olympic Peninsula and Vancouver Island. After clearing Port Angeles she was met by hundreds of Victorians who lined the Inner Harbour Causeway.

With pennants flying, Capt. Lyle Fowler berthed Chinook with 300 passengers and 50 cars at the Black Ball terminal. Opposite the Parliament Buildings, it was still under construction. “She is easy to handle and has a good speed,” he bragged to reporters.

Predicted PSNC president Capt. Peabody: “The travel industry between the mainland is bound to increase. We built the ship because we were aware of the growing interest on the part of the American public to the many advantages of a vacation and holiday in Victoria and on Vancouver Island.”

Victoria residents Mr. and Mrs. Harold Johnsonar were the first to land their car,“marking the inauguration of a new automobile transportation service between the United States mainland and Victoria”.

Those who inspected the new ship expressed admiration for her spacious design and plush appointments.

As indeed they should have, her owners having proclaimed her to be “easily the finest vessel ever put into [Puget] Sound service… No cost has been spared in decorating and furnishing, making the Chinook comparable to the finest hotel in comfort and [offering] a feeling of welcome to the traveler.”

After the dark war years, Chinook must have seemed a floating palace of colours and luxury. Her lobby walls were rose-beige, the rubberized floor rose-grey and the 14 staterooms were painted in calla lily green, with draperies of salmon hue, and cocoa-brown floors. The salon was decorated in the same colour scheme as her lobby with chairs in tones of rose-greens, walnut and yellow hues.

These were said to create “a most satisfying effect. Foam rubber gives added comfort to the furniture and the entirely double-stuffed frames of all pieces is an indication of the care with which details have been studied. Between the stanchions in the salon is a large, hand-carved Lucite map showing the typographical [sic] details of Puget Sound and the territory served by the PSNC.”

The After Lounge was a rainbow of mulberry and white with drapes of grey, chartreuse and deep violet. The furniture was in deep magenta, turquoise blues, yellows and grey. The Garden Lounge, forward, was in turquoise and white. Flower boxes of live plants and furniture of tile terra cotta in red, turquoise, walnut, grey and yellow were a final touch.

Victorians marvelled at the exotic hues and fittings. Even the ‘quickie’ dining salon (coffee shop) was resplendent in chartreuse and vermilion. What was said to be the last word in comfort and elegance in ferry travel (other than those interior colour schemes) sounds pretty tame by today’s measure.

M.V. Chinook presaged the provincial and state ferry systems that we have today

Her maiden voyage to Port Angeles and Victoria on June 26, 1947 heralded the arrival of the postwar ferry traffic. This would grow on both sides of the border to the present-day B.C. and Washington fleets.

After Victoria Mayor Percy George presented Puget Sound Navigation Co.’s Capt. Peabody with a Canadian flag for his new ship, M.V. Chinook went to work. Her ensuing career was of regular and dependable service, but not without excitement. Over the years she experienced a collision, an act of sabotage and a stranding.

The first near-disaster occurred just five months after she entered service. She and the Swedish freighter Dagmar Salen rammed off Puget Sound’s Bush Point. Both ships were equipped with radar . But Chinook’s crewmen later testified that they’d been unable to see more than five feet ahead and the freighter didn’t appear on their radar screen until moments before impact.

The ferry’s several hundred passengers were thrown into momentary panic. Some screamed, reported a Seattle passenger, “rushing out of the lounge toward the lifeboats, or to the lifebelts in their cabins. A lot of broken glass from the ferry’s windows was thrown around the lounge, but I didn’t see anyone cut. The impact knocked the legs off several chairs and broke an ornamental bronze railing near the lounge windows.”

The result of a collision, one of the M.V. Chinook‘s few close calls with disaster in an otherwise illustrious career.

Both wounded vessels proceeded to port under their own power. Although a survey of Chinook’s damage revealed that the port wing of her bridge had been sheared off and some plates above the waterline buckled, she maintained her work schedule until her scheduled refit.

Despite this inauspicious beginning, by the end of her first year of duty, Chinook had carried 135,000 passengers, 42,000 vehicles and 91,000 tons of freight. Between Seattle, Port Angeles and Victoria, she’d chalked up no less than 100,000 miles.

In 1952 Seattle was dropped from her run. In May 1955 it was announced she’d join the company’s Nanaimo-Horseshoe Bay route, Black Ball having made the decision after “two years of intensive study”. At that time, Horseshoe Bay was B.C.’s busiest ferry terminal.

This change of route was unpopular with some

Victoria protested loudly, a city commissioner and head of the Island Publicity Bureau terming Chinook’s removal “the greatest blow ever suffered by the tourist industry here”.

But the decision was final. On June 4, Chinook began her new run in the Strait of Georgia. Six years later, the expanding B.C. Ferry Authority bought the Black Ball’s Horseshoe Bay and Howe Sound services. Included among the $7 million purchase of five vessels, two terminals and several smaller docking facilities was the onetime Queen Elizabeth of the inland seas, Chinook.

Renamed Chinook II, the numeral denoted her change to Canadian registry. (In 1964 she became Sechelt Queen by which name she finished her 35-year-long career as a ferry.)

Months later Chinook, now Canadian in name and in fact, and other former Black Ball sisters debuted in the Dogwood Fleet colours of white and blue.

There were two minor incidents during her first years under the provincial flag. One was the striking of a bluff in Horseshoe Bay while dodging a small boat. The second when she became ensnared in a boom chain when caught by wind and the wash of another ferry. Skin-divers had to cut her propeller free.

Her closest call with disaster came on the morning of April 5, 1962. This was just 90 minutes after Capt. Roy Barry had eased her, with 70 passengers and 40 vehicles, from Horseshoe Bay. “Following an uneventful crossing of Strait of Georgia,” to quote Cadieux and Griffiths in Dogwood Fleet, “she approached the entrance to Departure Bay. The entrance is not wide and but a cable [200 metres] or so on the port side lies Snake Island, a barren ridge of rock popular only with nesting seagulls.

“As the area loomed nearer, a bank of fog was seen to shroud the coast, Capt. Barry took off speed. His radar gear was ashore for refit and he was running with the traditional tools of the pilot–time, speed, direction, distance and judgement. The fog closed in and Barry reduced to dead slow…”

Abandon ship

For all his skill, however, he was 700 metres off his course. With little more than a muffled thump, the 3300-ton ferry struck hard around, her bow fast on the rocks with an ebb tide steadily dropping her stern. Passengers in life jackets were shuttled by volunteer small craft to Nanaimo and the Gabriola Island ferry Eena. Chinook was re-floated eight hours after striking.

Three months later she returned to service. She suffered further misfortune when a bomb consisting of two sticks of dynamite and an alarm clock exploded in a lifebelt locker. Aside from splintering the locker and adjacent windows, the blast, allegedly planted by a fanatical religious sect, did little damage.

After a major refit in 1969 she was shorn of her bow for improved fore-and-aft loading. As Sechelt Queen she was sold in 1982 for use as a floating fish processing plant. She returned, as the Muskegan Clipper, to the U.S. where she was sold for conversion to a casino. But, instead, she was stripped to her hull in 1997 and “likely scrapped.”

Now the good ferry Kalakala has joined her co-worker in the annals of Pacific Northwest maritime history.

C

C

There are so many wonderful stories to discover in terms of our nautical history here in the Pacific Northwest. This is another terrific telling of a ships lifestory, TW, I had no idea and I really enjoyed it a lot!!

I like to joke that I’ve ‘sunk more ships than Lord Nelson’. And indeed I have, in print!

Hundreds of ’em.

But I also like to profile ships of character, ships with not just a colourful history but a successful working career. Certainly the good ferry Chinook is worthy of honouring.

What a shame that the one-of-a-kind Kalakala has gone to the breakers after all these years. I can remember the first time I set eyes on her, as a kid in Victoria. I thought she was ugly! That was before I cam to appreciate her art-deco for what it was, a character statement.

Please keep reading. –TW

What a great read. I read with interest in search of a old ferry I seen on a trip up the squamish railroad on a steam train in the late 80’s. Took my family on the squamish steam train for a nice afternoon. Along the trip I noticed an old ferry moored on shore maybe about half way to squamich. I was very taken with its beauty. I never forgot the image, it had looked to not be in services for some time. For the life of me I can’t seem to find a picture of it. Not sure of the name that was on it, it was moored with the back facing the shore. Sure would love to find something out about that beautiful ferry. Randy

Hi, Randy. Several former B.C. Ferries vessels have been bought by private parties. I saw one moored (the Sidney?) somewhere on the Fraser River delta the last time I was in that area, some years ago. She looked pretty sad. Some former ferries have been used as fish plants and the like but most, I believe, have gone to the wreckers. Pretty expensive toys, I should think! –TW