Canadian $10 bill kerfuffle recalls martyred nurse Edith Cavell

Oops. There was a mistake on our new plastic $10 bill. It only took the Royal Canadian Mint eight months to correct, if not admit, that they goofed on their photo of Mount Edith Cavell.

According to the Canadian Press, mountain climber Hitesh Doshi spotted the mistake: a mountain that was identified on the RCM’s website as 3363-metre Mount Edith Cavell in Jasper National Park was actually Lectern Peak. After laying the blame on the Canadian Bank Note Co., the Mint assured us that all is now well.

So who was Edith Cavell and why did they name a mountain after her?

For answer, I’m going to quote myself from my 2005 book, A Place Called Cowichan:

A century and a second global conflict have passed since the ‘war to end all wars’. [Duncan’s] Ypres, St. Julien and Festubert streets honour some of its forgotten battlefields, as does Cowichan Lake’s Hill 60.

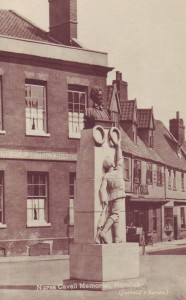

Cavell Street also hearkens from the First World War but is named not for a battlefield but for a heroine, Edith Cavell. Her death before a German firing squad made her a household name for a time.

Driven by the same desire to serve as her idol, Florence Nightingale, Edith Cavell first achieved notice for her medical work in the slums of London in the years immediately following the turn of the last century. She attracted the attention of a Belgian surgeon, Dr. Antoine Depage, who was distressed by a lack of scientific nursing in his own country. He persuaded Edith to establish a nursing school in Brussels.

Edith Cavell ran a tight ship

Within a few years Edith, then in her 40s, was matron of the Berkendael Medical Institute, with a staff of 50 trained nurses. Her trainees of several nationalities had to accept hard work, discipline and dedication. Edith was fiercely protective of them and won their loyalty. She took her responsibilities seriously, rarely smiling, rarely revealing her private self. The daughter of an English clergyman, she was devout to the point of being ascetic–a born martyr.

When the Germans occupied Belgium in 1914, Edith and her English nurses remained to treat war casualties, Berkendael Institute having become a Red Cross hospital. She began helping Allied prisoners of war to escape from behind German lines. Her hospital became part of an underground railway.

Twice German soldiers ransacked the hospital without finding anything incriminating. On their third visit they arrested her. She made no further attempts to deny her activities, declaring that she’d done her duty in helping to smuggle 103 servicemen across the Dutch frontier.

Convicted of harbouring and aiding the enemy, Edith Cavell was sentenced to death

Pleas for clemency by American officials (that country did not enter the war until 1917) failed to deter German authorities. They were determined to make an example of her and a Belgian national convicted of the same charges. She and her fellow prisoner were driven to a rifle range where she was blindfolded and her face covered with a black veil. A witness was struck by the contrast of her blue nurse’s uniform against a wall of German grey.

From the moment of her arrest, Edith had maintained a stoic calm. But as the firing squad took aim, she fainted. Rather than revive her, the commanding officer knelt by her side, placed the muzzle of his pistol against her temple and pulled the trigger.

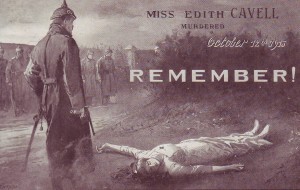

The Germans had acted strictly in accordance with international law. But their insistence upon the death penalty handed Allied propagandists a plum. Thousands of postcards bearing an artist’s conception of her death and the legend ‘cowardly murder’ were distributed.

One version bears this gruesome and sensational account of her execution: “Condemned to death by a military tribunal in Belgium, under the charge of having favoured the evasion of British soldiers, miss [sic] Edith Cavell of Norwich, a voluntary nurse, is taken to the execution ground…at daybreak. She faints; the German officer gives his soldiers the order to fire; they hesitate to shoot on the prostrate body of a woman. The fiend takes his revolver and leaning upon his victim, deliberately blows her brains out. REMEMBER!”

In Duncan, B.C., King’s Daughters Hospital and Convalescence Home, on the site of today’s Cairnsmore Place Extended Care facility, was opened April 4, 1911. Four and one-half years later, Edith Cavell’s death made world headlines and led to the christening of adjacent Cavell Street. It’s only a block long but, fortunately, Mount Edith Cavell on the B.C.-Alberta border also honours this heroine.

Tom,

I couldn’t find a general contact so I’m using this location. I would like to share some information with you about Byron C. Riblet.

Hi: You’re referring to the man who built the tramline for the Tyee Copper Mining Co. on Mt. Sicker, of course. It worked well, sending the core down the mountain from the mine to the E&N Railway line, from day one. When the Tyee closed, the cables and equipment were recycled at another copper mine in the Alberni Inlet area. I have some bits and pieces the salvagers missed in my musueum. Up until about five-six years ago, at least two of the old towers were still standing. Loggers knocked them down, alas. Thanks for writing. –TWP

What a story, TW. Wow, I had no idea once again of the history that lies in our very own backyard here. I will never forget this story, thanks for sharing it.