Was Thigh Bone the Remains of Lost Airman?

What puzzled Ildstad most was the absence of clothing or foot wear–just bone fragments.

The west coast of Vancouver Island is honeycombed with limestone caves, many of which were used as natural mausoleums by First Nations peoples.

But, sometimes, they contained non-Aboriginal remains that posed so many questions as to relegate them to the status of mystery.

(Of the 179 airmen known to have been killed or gone missing while training to fly at Patricia Bay Airport during the Second World War, many still haven’t been accounted for. Their final resting places in the B.C. wilderness as yet unknown. –See also Mount Bolduc bomber wreck a WW2 Tragedy.)

While timber cruising near the southern entrance to Quatsino Sound in the summer of 1947, the late Guy Ildstad found a small cave on the shore of Gooding Cove: “Some slight shelter is afforded by small islands and reefs,” he recounted almost 40 years ago, “[but] in high tides and storms great breakers sweep the cove, and reach the floor of the cave.

“The entrance is high enough for a tall person to walk upright, but the roof slopes down toward the end–about 35 feet deep–where it pinches out, and one must crawl to reach the limit…”

The cave is at the base of a 1,600-foot mountain that rears from the sea, so sheer, he said, that it’s impossible to scale. To reach the cavern, one must begin climbing down some distance to the west. Even there, the going is rough, but Ildstad, the son of a pioneering Quatsino family, was up to the task that day and, intrigued, he entered the hole in the cliffside.

Halfway in, he was surprised to see the embers of a fire. “I stopped and looked around, and found bones. They were scattered and lying apart but I picked up one that looked like a human thigh bone, which I carried home when my work was done some days later.”

He showed it to a medical student who pronounced it to be human. Its length, 16 inches, indicated a tallish man.

His first thought was that it must be Native. But they “would almost certainly not use a place where flood water could reach the dead”. Also, the bones were not old enough. While there is tell-tale evidence of old Indian camps or dwellings near the site they would necessarily have had to be more than 60 years old [as of 1966 when he told the author this story], according to settlers who came to Quatsino and Winter Harbour in 1897.

Another apparent indication of comparatively more recent vintage was that the fire appeared to have been lit with matches. Even this modern aid would not have made a fire an easy task in the rain forest without an axe. What puzzled Ildstad most was the absence of clothing, foot wear or camping gear–just the bone fragments.

Foraging animals would account for the bones being scattered but not for the lack of clothes and effects.

“What brought the person to the cave?” he wondered. “Was it…some survivor of [a] shipwreck or plane crash reaching this place, starving and exhausted, entering the cave seeking shelter? And then, having reached the end of his endurance, overcome at last by lack of food and strength to scale the high rocky walls, breathed his last?”

Six years later, Ildstad and two partners were prospecting near Lawn Point, nine miles south of Gooding Cove. One Sunday, having some hours free, they visited the site of a plane wreck, two miles from their camp.

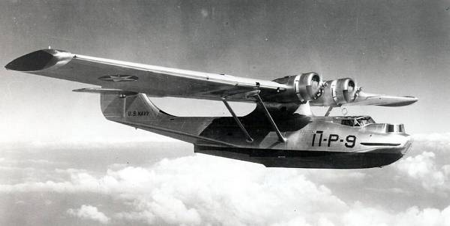

“Rose bushes were growing to the level of the wing. The undercarriage was still there, though utterly wrecked. Inside were two sub-machine guns–with ammunition belts ready for firing.” A live bomb on board the PBY, which crashed in December 1941, had also survived the impact and subsequent fire and was later detonated by an air force team.

When fishermen originally spotted the plane wreck three months after it went down, they found the bodies of all but one of the crew laid out under a collapsed wing, apparently placed there by the survivor.

No trace of this airman was ever found although Ildstad said “he could not have been badly injured as he had carried driftwood from the shore for his fire–more than 200 feet away, and all up-hill”.

Did he finally “set…off along the rocky shore where a strong man can make no more than one mile per hour? Not only is the travelling slow and rough,” he noted, “it is dangerous as well. For often jutting rocks force the wayfarer away, up from the beach. At other points it is possible to await a receding wave to leave a passage along the base of a cliff.

“But it is a dangerous thing to do, for should an incoming sea reach anyone attempting this perilous route, he would be swept off his feet and dashed on the rocks.”

Did the surviving airman make it as far as the cave in Gooding Cove where he was overcome by hunger, exhaustion or hypothermia? We’ll never know. Years after he carried it home, Ildstad threw the thigh bone away.

See also: Mount Bolduc Bomber Wreck a WW2 Tragedy

T.W Paterson also publishes www.CowichanChronicles.com.

Hello, the crash at Lawn Point was not a PBY it was a US Navy Ventura (PV-1 28736). But I am confused because the likelihood of two WW2 planes crashing on Lawn Point is highly unlikely. The Ventura crashed there in Dec 1943 and was discovered by a CFS patrol in 1944, not fishermen. It was the Ventura crew that were laid to rest by a crew member Joseph Anderson, Ogden, Utah, who was never located. Seems like there are two stories interwoven here with some facts correct but some not so.

Thank you for this, Petey. I originally wrote this story 20 years ago, taking it from my interview files, in this case Mr. Guy Ildstad. Since then I’ve researched many of the military plane crashes in the province during WW2–but I didn’t check them before posting this article. You’re right, we’re probably talking about the same plane crash. I’m going to pull my wreck files and check further. Please let me get back to you, TW.