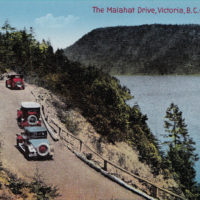

Island Highway’s Malahat Stretch Has Always Challenged Motorists

The Malahat is in the news again. In fact, the Malahat, Greater Victoria’s vital mountainous link to the rest of Vancouver Island, has been in the news repeatedly this summer because of almost weekly accident-caused traffic stoppages.

25,000 vehicles use this 20 kilometre-long stretch of highway daily.

It seems, sometimes, as if it has ever been thus: the calls for widening, or a by-pass, or a tunnel, or a bridge or improved ferry service across Saanich Inlet. Or a revived E&N Railway commuter train or a busline using the railway grade. Or a combination of any and all of the above.

Why doesn’t the damn government do something?

Most recently, Vancouver Sun columnist Vaughan Palmer got into the act with a study of the challenging and expensive problems facing politicians and planners who must deal with a growing chorus that they “fix” the Malahat.

The real problem, as becomes apparent if you drive the Malahat often, is not so much its curves and steep grades but that most drivers ignore posted speed limits and push their—and hapless others’—luck, often to the breaking point.

Come winter, of course, nature also plays a role.

But all that’s a modern-day phenomenon and I’m supposed to be an historian, right? So, as such, it occurred to me to dig into my files and tell you something of the Malahat’s colourful history.

By Malahat, I mean both the mountain and the highway.

The Mountain (officially a ridge), obviously, came first. So did the Malahat First Nations for whom it’s named.

The first wagon road avoided the Malahat altogether, wandering from the last pit-stop of civilization, the Goldstream Hotel, around Sooke and Shawnigan Lakes and eventually to Cobble Hill. This route, unlike today’s highway, was slow, torturous and treacherous for man and beast. For years, even after the building of the E&N Railway, various individuals and groups agitated for a proper roadway to connect Victoria with the rest of the Island.

With the coming of the horseless carriage demands for improved roads steadily increased. During the Dominion Day weekend of 1907, 15 automobiles of the Victoria Auto Club organized a Victoria-Alberni rally to publicize the deplorable conditions of the so-called Island Highway.

Even then the spectacular ocean views were a draw.

A Victoria Colonist editorial was prophetic when it urged the provincial government to improve the up-Island roadway, suggesting that it would “create a paradise for automobilists which would no doubt be sought by tourists from many parts. The result would also undoubtedly be a more active demand for motor cars than now exists in Victoria. Everybody who could afford to purchase would possess one.”

Originally, those who did brave the Malahat did so on foot, following long established Indigenous trails, and had to carry their goods on their backs. Today, much of the credit for the building of a road from Mill Bay to Goldstream goes to former Royal Artilleryman, Maj. J.F.L. MacFarlane.

He didn’t do it alone, Francis Verdier, known as B.C.’s oldest timber cruiser, having played an instrumental role. Suffice to say that Maj. MacFarlane succeeded in lobbying the government by collecting a nine-foot-long petition in favour of a shortcut over the ‘Hat, and he had the honour of being the first to drive, in his horse and buggy, between Mill Bay and Victoria.

An improvement, yes, but still a driver’s nightmare.

It may have been a shorter route than by way of Sooke, but it was hardly user-friendly. Many are the horror stories which have been passed down over the years of navigating the steep, narrow and winding goat-track. Fifty years ago, cash register salesman C.G. Owens, who often braved the Malahat in his 1912 Chalmers, recalled: “The mist used to get so bad, we’d have to pull over and wait for it to clear. The [carbide] lights wouldn’t cut through it. Once you got rolling, you didn’t change your mind. There were stretches of that road which seemed to go on forever without a place to turn around.”

An up-Island run to attend the Cowichan Bay Regatta took him five hours. Some claimed to have made it in three—if they made it at all. “We used to find some of these speedballs’ cars skittered off the side of the road and up against the stumps,” said Owens with an obvious self-righteous chuckle.

Many other oldtimers told of driving the Malahat when headlights, such as they were, hardly dented the darkness, axles snapped, radiators boiled over, brakes burned out and tires failed almost every mile.

(One of my favourite anecdotes about old cars concerns the man who drove into Plimley’s garage in Victoria to have five flat tires repaired. Told they could only fix one on the spot, he snapped, “Good God, man, I’m driving to Goldstream!”—10 miles from downtown Victoria.)

Driving over the Malahat was an adventure,

recounted Victoria’s first woman driver. Mrs. E.M. Hopwood said there were no “railings on the edge, and it was a one-lane road. If you met another car, one of you had to turn off the side of the road into one of the turn-offs [she obviously came after Mr. Owens] so that the other could get by.” Her first trip over the ‘Hat cost her a set of brakes.

To cater to the growing traffic, Algernon Pease built Hamsterly Malahat immediately south of the Lookout in the 1920s. Robert Buller built the Malahat Lookout, which survived until September 1953, when it was destroyed by fire, its occupants barely escaping with their lives.

The highway was modernized in 1956. Ironically, the number of fatalities has increased along with higher speed limits. But the scenery is as breathtaking as ever.

PS:

Since I’ve borrowed from my book A Place Called Cowichan for this post. I should note that its Indigenous name ‘Malaha’ means “infested with caterpillars,” a reference to periodic tent caterpillar infestations. Another name for the mountain, ‘Yas,’ means ‘home of the thunder.’

To the E&N, the peak of the Malahat was the Summit until 1911 when it recognized Malahat. The railway’s version of its name origin means ‘plenty bait,’ a reference to the waters of Saanich Inlet at the foot of the mountain.

Prior to the railway, the Cowichan Valley was accessed by weekly steamship service via Cowichan and Maple Bays. Locals would order a year’s supplies at a time, wait a month for delivery to the nearest dock, then have to haul it all home by horse and wagon.

And today’s commuters think they have it tough.

There’s much more to the story of the conquering of the Malahat by roadbuilders and I shall return to the subject in a future post.

—Excerpted from A Place Called Cowichan: Historically Significant Place Names of the Cowichan Valley, T.W. Paterson.