John Cowley Preferred Flowers to Gold

John Joseph Cowley was one of the legion of hopefuls who sought to make his fortune in one of British Columbia’s several gold rushes.

Few, in fact, of the tens of thousands who tried even recovered their expenses before having to go to work for those who’d been “lucky” or return to their previous occupations.

Among these for the most part anonymous also-rans was John Cowley whose diary, today in possession of the British Columbia Archives, provides fascinating insight into what it was like to uproot one’s whole life and travel as much as halfway round the world to look for gold–but not find it.

Little, alas, is known of John Cowley.

He gives no hint of his background other than that he appears to have come to B.C. from Ontario. Mr. Justice R.A. Wootton of the B.C. Supreme Court, who inherited his pencilled journal that spans a nine-month period through early April to late December 1862, barely remembered his parents having told him that Cowley “was a keen naturalist, a collector [who] was also artistic.”

This is clearly indicated in the diary. As others clawed their way over mountaintops and worked waist-deep in ice-cold rivers for gold, Cowley gathered specimens for which he was mentioned in the Cariboo Sentinel in 1869:

“Mr. Cowley, of the Rocky Point Company, Grouse Creek, has collected a sample of the various kinds of moss found in Cariboo, and preserved them in a large glass case… [He] has, during the past summer, discovered a variety of indigenous fruits and among them was a splendid sample of red currants.”

Perhaps Cowley found no gold because his heart really wasn’t in the job of prospecting.

Mind you, his introduction to gold mining, 16 months before, had not been an auspicious one–he’d broken his leg in a rock slide and had had to wait, in agony, for a day for a doctor to treat him.

It’s interesting to note that, for all of Cowley’s interest in natural history, his formal education seems to have been somewhat limited if one judge’s him by his spelling. His first entry of April 8, 1862 records his party’s arrival in New York City. He noted not only some of the Big Apple’s botanical treasures but, after visiting a saloon and a dance hall, that the atmosphere was decidedly “free and easy. Almost one-half of the women in city said to be of easy virtue; 15,000 prostitutes”.

From there he sailed to Panama on a ship whose food was “more fit for hogs than men; awful filthy. They [officers and crew] treat us more like beasts than human beings. Water closets a disgrace. Have not eaten a[ny]thing at the table or of the ship fare [he’d wisely brought his own provisions aboard]. Hard to tell what their coffee and tea is made of…”

Fair weather, continuing rumours of the richness of B.C. gold fields and the panorama of wildlife kept him from becoming discouraged during lay-overs in Panama and South American ports as his steamer sailed south to round Cape Horn, then up the west coast to Acapulco and San Francisco, at which port he arrived, early Sunday, May 18.

Unlike his previous stops, he found the Bay City to be “very fine…[with] some good buildings,” although its streets were too narrow and in disrepair. Three days later, 500 passengers boarded the steamship Pacific for Victoria.

She was so overcrowded that Cowley and his companions had to sleep on deck with a cargo of mules and horses.

On May 28, 1862, a Wednesday, they landed at Esquimalt and hiked to Victoria, which he found to be enchanting, “a most beautiful site to build a city”. After the rigours of shipboard life, John Cowle’s party turned eagerly to hunting and fishing (likely in Saanich), the ever-observant adventurer noting that, although they returned empty-handed, he’d sighted ducks, several smaller (unidentified) birds similar to those he’d seen in Ontario, “also many wild flowers among which was blue larkspur…”

He even found time to try a little recreational prospecting–in Beacon Hill Park.

A week later, they engaged the sloop Louisa to take them to Stikine River. Because of light winds it took them four days to make it as far as Nanaimo which he described as a “nice little village”. On June 26, 1862, just under three weeks after clearing Victoria, the Louisa, now one of a fleet of vessels, arrived at Fort Stikine.

With scores of other hopefuls, John Cowley and party camped ashore while awaiting the steamer Flying Dutchman to return from up-river.

“The river is yet very high and said [to be] very difficult to ascend in canoes,” he pencilled in his tiny diary that, today, is in possession of the B.C. Archives. “…We pitched our tents alongside the rest, in which we stowed our provisions and made a very comfortable [bed] of hemlock bows [sic] and our blankets. The mosquitoes are very numerous and disagreeable.”

They were so disagreeable that sleep, even beneath a blanket, was impossible. But their nocturnal discomfort was forgotten upon the steamer’s return with “good accounts” from the upriver diggings. Their 80-mile passage aboard the Dutchman cost them $3 each, their supplies and canoe, $4.

Two days later, the steamer dropped them on the bank of the forbidding Stikine and they continued upstream by rowing and making use of a tiny sail which soon failed them for want of a breeze.

July 3: “Had [to] row and paddle and sometimes get out and tow, got on sand barrs [sic] several times and had to get out to get off. While towing across a narrow channelle [sic] with gum boots on, I got stuck in quicksand and fell down, so got up wet to waist. Got to a difficult rapid where we rowed for about an hour without making headway, when a breeze sprang up about 6 p.m. and we hoisted sail and arrived at the generall [sic] company ground at 7 p.m. It is about 75 miles from the mouth of the river and some say 10 from where the steamer landed us.”

They continued upriver. Despite their having lightened their load by arranging for their supplies to be taken by steamer, their progress was slow and difficult as the river was continually blocked by rapids and snags that forced them to tow their canoe.

For all of the hardships, Cowley couldn’t resist noting the wildlife, remarking in his journal that he hadn’t seen any frogs since leaving Ontario, although there had been the occasional toad.

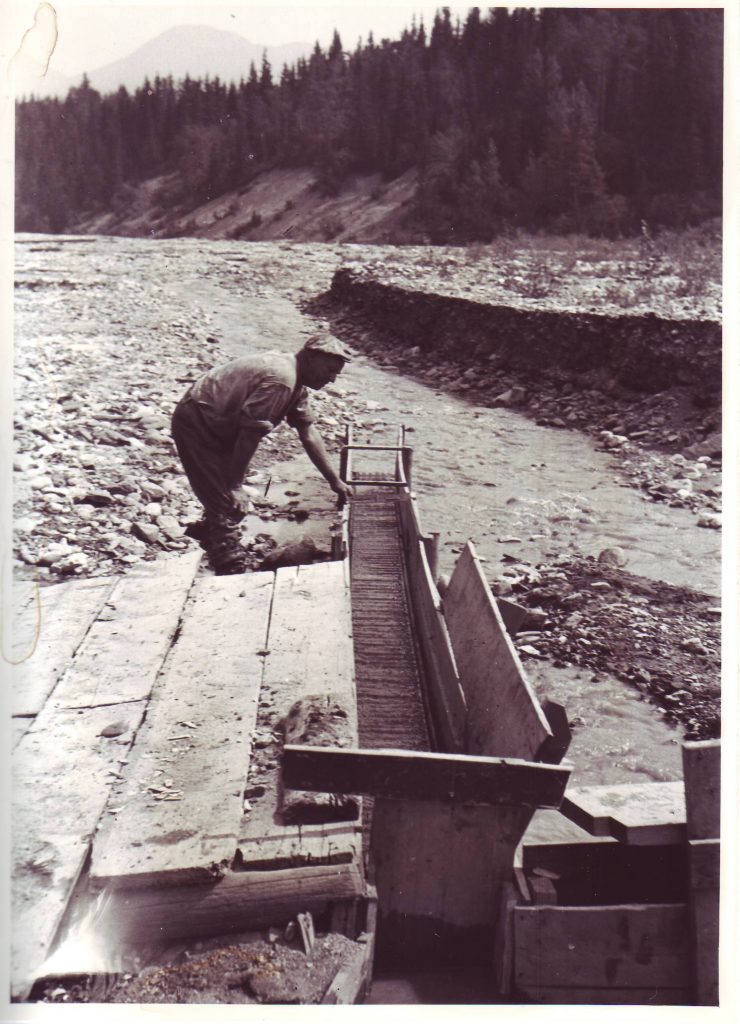

A mile above Shakesville, they located their claim. When, due to spring run-off, their initials efforts at panning were “very dull,” they set to work with a rocker. Partners Geary and Cummings washed 25 buckets of dirty water and earned 40 cents for their trouble. They blame their rocker for being too small to catch all of the gold.

[sic]

Cowley and three companions speared salmon and picked a pint of red currants (which he found to be much like the eastern variety but “rarther longer than round with thin and transparent skins”), some “raspberries,” strawberries and two varieties of gooseberries.

Electrified by the news that a miner was earning $50 a day, two of Cowley’s party headed upriver, leaving the rest to work their present claim. They worked hard, too. On July 23, Cowley and Harding washed 150 buckets of gravel–earning 60 cents–“which is rarther [sic] discouraging, but we hope to do better tomorrow, it not being the best pay dirt.”

The next day, fewer buckets yielded $2.30.

After an exhausting shift, Cowley went pigeon hunting and had to settle for black currants. Friday, July 25, they netted $2.40–and Cowley saw his first frog since leaving Ontario. Much to their consternation, rainstorms caused the river to rise three feet, further reducing their chances of reaching any gold-bearing gravels.

Cummings returned for more supplies and reported that the upstream claims were paying well. But they stayed where they were and, despite rising water, had their best daily return to date, $4. Geary celebrated by shooting four squirrels for a stew.

Next day, Cowley, Geary and Cummings picked berries, the former noting: “Our claim pays so bad we won’t work it till we are obliged for want of a better which are heard [sic] to find. The prospects are very dull for this year as yet.”

Upon learning that things upriver weren’t much better, they headed downstream, having to battle heavy rains and rapids for five days. Cowley must have been exhausted by it all as, for two weeks, he recorded only the weather, and doesn’t mention their new claim until August 25th when he merely wrote that they’d dammed a slough.

On the 31st, he mentioned picking five quarts of wild currants and shooting five grouse.

With the weather rapidly cooling, they ranged farther afield in search of prospects, panning every likely spot but finding only some traces of what they took to be silver. On October 6th, they boarded a southbound schooner for a stormy passage to Victoria and arrived just in time to celebrate the Prince of Wales’ birthday by attending the horse races in Beacon Hill Park.

“The town has grown wonderfully,” he wrote after his five-month absence–so much so that they had to go to Esquimalt to find accommodation.

To meet expenses, Ralph cashed in the gold that it had taken him all summer to earn: $16.50.

To see them through the winter, he and Cowley contracted to assemble a prefabricated iron house for $55 and, on December 17, finances improved with Cowley depositing $100 in the bank before accepting work as a longshoreman for $2.50 a day.

The final entry in his diary, for Saturday, Dec. 27, 1862, covers a Christmas outing to Nanaimo. As late as 1872, John Joseph Cowley is known to have been in the Cariboo, likely as a miner.

Alas, any further diaries he may have kept have been lost. He died in Victoria in 1909.

Wonderful story!lived in the caribou and esquimalt.

Thank you, Angela. –TW

Wished his Cariboo diaries had not been lost.

One can only wonder how many truly great and valuable diaries/journals/log books have been lost–or worse, destroyed–over the years.

I was looking for an article written about Thomas Crosby and Snuneymuxw convert David Sallosalton…Hopefully it is still available. With thanks Bill White

I know the one you mean, Bill; it’s an old Cowichan Chronicle in the Cowichan Valley Citizen. You’ll have to give me a few days to dig it out–I’m always up to my ears in deadlines. –TW