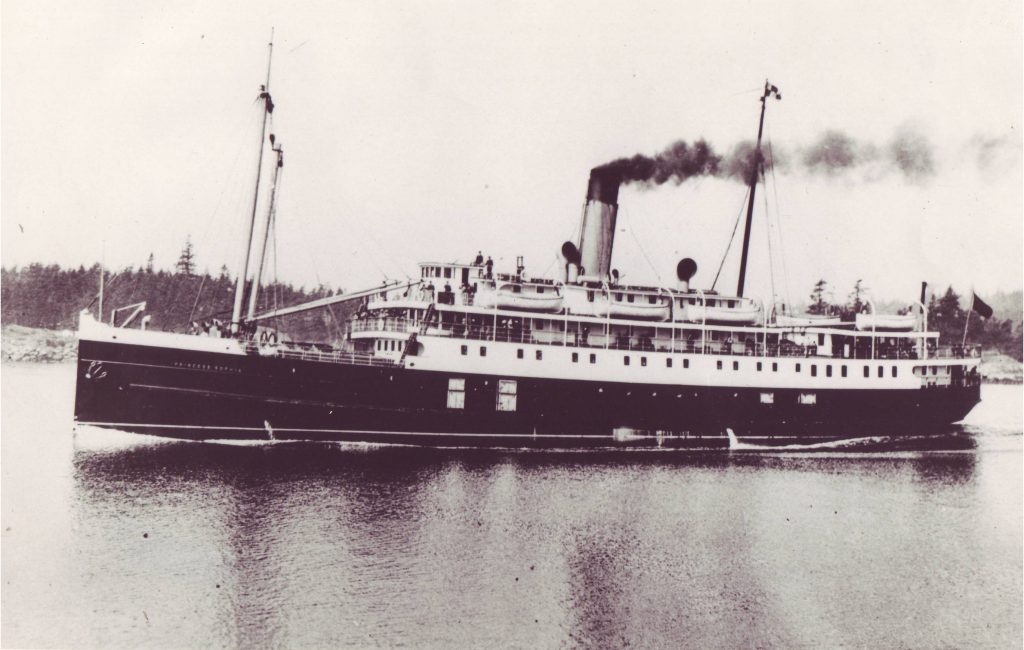

October 25, 1918: Canada’s ‘Titanic,’ Princess Sophia, Sank 100 Years Ago

Canadian Pacific Steamships’ coastal liner Princess Sophia has been compared to the Titanic because of the appalling loss of life, 343 men, women and children.

Unlike the Titanic, not a single soul survived.

The Titanic struck an iceberg in the North Atlantic, the Sophia grounded on a reef in Alaska’s Lynn Canal. Even though she sank in American waters, the Victoria-based coastal passenger liner is recognized as British Columbia’s worst shipwreck ever…

“Just time to say goodbye. We are foundering.”

This pathetic farewell of 343 passengers and crew was flashed through the night of Oct. 24, 1918. Then silence.

Anxiously, the rescue ships bucking gale-swept Lynn Canal listened for more. But the S.S. Princess Sophia was never heard from again.

With morning came calm, but only a mast tip marked the 2300-ton pocket liner’s grave by Vanderbilt Reef. There was not one survivor.

Winter had struck the west coast early and hard in 1918. Driven off course during a blinding snowstorm, the Sophia grounded on Vanderbilt Reef early on the morning of October 24 and stuck fast. Capt. F.L. Locke, a veteran of 27 years’ service with Canadian Pacific, immediately radioed particulars of his situation to his company, the B.C. Coast Service.

Capt. Locke didn’t think his ship was in danger.

Both he and senior company officials believed that the Sophia would float off the reef on the next high tide, expected that afternoon. The salvage steamer Tees, just returned from rescuing the CPR steamer Princess Adelaide from reefs at Georgina Point, prepared for immediate departure from Victoria.

Aboard the Sophia was one of the largest lists of passengers handled that year. Most were from the interior of Alaska after reaching Whitehorse, Y.T. on the last boats before river navigation closed for the winter. They were southbound to enjoy the season in a more pleasant climate and, sharing Capt. Locke’s confidence that the Sophia would float free, they whiled away the time calmly.

Both Victoria newspapers, the Times and the Colonist, gave the story prominent and thorough coverage, providing the latest details to a news-hungry city all too familiar with marine disasters. Victorians followed the news reports closely, speculated amongst themselves and…waited.

CPR news releases were encouraging.

“The waters of Lynn Canal [where many would recall that the passenger ship Islander had gone down with great loss of life after striking an iceberg 17 years before] are well protected, and no loss of life is expected…”

When Sophia failed to float off on Thursday’s afternoon tide, officials insisted that the ship was in no immediate danger, that the Tees would proceed to the scene, that the company’s Princess Alice had been dispatched to perform a transfer of the passengers, and that “If the weather holds fast, there should be no difficulty in getting the Sophia afloat on the tides which occur early next month.”

Press stories unwittingly carried the first hints of tragedy when they reported that “a fresh northerly breeze” was blowing down the canal and making a transfer of passengers to any of the vessels that were by this time standing by.

These vessels were the American ships Cedar and Peterson, the auxiliary schooner King & Wing, and many smaller craft, most of them fishing vessels.

CPR officials remained optimistic.

They appeared to be more concerned about the disrupted passenger services which required that they juggle schedules and steamers in an attempt to keep all routes operating.

However, while admitting publicly that they were having increasing difficulty making contact with the Sophia, they reassured Victorians that all would work out well; and should the situation deteriorate, the small fleet of vessels on the scene would take care of all those on board the stranded ship.

The announcement of Sophia’s sinking hit Victoria like an earthquake.

People weren’t just shocked, they were numbed. A brief wireless message had been relayed to Victoria from Juneau, stating that, some time during the night, the ship that had made Victoria its homeport since arriving from a Scottish shipbuilder, had sunk.

In some quarters the news was received with disbelief. Capt. J.W. Troup, manager of the B.C. Coast Steamship Service, said: “It is hardly conceivable. I cannot believe it.” He desperately tried to get official confirmation or denial from Alaska. Because the telegraphic cable to Skagway was out of commission, the only means of communication was by wireless, then in its infancy and never too good at best of times.

Upon hearing the report of her sinking, many Victorians held the hope that those on board had been picked up by the fleet of rescue craft standing by.

Except for the initial wireless report that Sophia was gone, Victorians knew nothing.

They impatiently waited for Princess Alice to reach the scene. With her powerful transmitter she’d be able to report the situation in full.

Whent he U.S. lighthoue tender Cedar received Sophia‘s message that she was foundering, about 5 o’clock p.m. Thursday (the 24th), she’d radioed back, “We are coming. Save your juice so you can guide us.”

But in the storming blackness the little tender was forced to put about and anchor until daylight. At 8:30 the next morning, she radioed Alaska that only the Sophia‘s foremast showed above water.

By then the storm had passed and the would-be rescuers were able to walk, at low tide, over Vanderbilt Reef where the Sophia had perched. The rock where the hull had rested was worn smooth “as a silver dollar” by the grinding action of the ship.

Apparenty heavy gusts quartering on her stern, whch wasn’t held up by the reef, swung her around, the bow acting as an axis. When the bow was blown free, she filled by the head and sank. It all happened quickly and unseen by the vessels standing by.

In the five days before Sophia‘s last sailing, more than 800 persons had reached Whitehorse and Skagway en route to the outside. They’d been disappointed to find that practically no shipping accommodation was available. However, more than 300 had been able to board the Grand Trunk Pacific steamer Prince Rupert which had made a special trip north.

As the Rupert slipped from the Skagway dock, the crowd aboard cheered their good fortune. But those standing on the pier, faced with spending the winter there, watched her departure in silence.

How ironic then that they did cheer when informed that the Princess Sophia would make another trip; 258 men, women and children boarded her.

The heartbreaking task of collecting the bodies began under the personal supervision of Alaskan Governor Riggs. At least 25 vessels participated in the recovery operation. The shores lining Lynn Canal were littered with victims. Many bodies of women and children were found on life rafts, indicating that an attempt had been made to save them first. They died of exhaustion and exposure.

It was learned that passengers had refused the opportunity to be taken off before the storm, preferring the warmth and comfort of the ship to the cold and barren shores. In this the barometer had performed a cruel deception—it had been rising, indicating an improvement in weather.

Of Princess Sophia‘s crew, many of whom had made their homes in Victoria, one escaped. Chief Engineer A. Alexander was on vacation.

One of the more poignant incidents of the wreck concerned 17-year-old Norman Blyth. He’d been hastening south to the Shoal Bay bedside of his mother who was dangerously ill. He’d made repeated atempts to secure transportation home but had been unsuccessful because of the heavy end-of-season bookings. Aware that his mother might not recover, he’d made a last desperate effort and managed to get a berth as a steward aboard the Sophia.

Mrs. Locke, wife of the Sophia‘s captain, was shopping when first word of the sinking rached Victoria. A young boy ran up to her, crying, “Mrs. Locke, the Sophia is sunk and your husband is drowned!”

Victorians joined Skagway, Jueanu and Whitehorse in mourning. Then, still numbed by the blow, Victorians received another cruel shock. Exactly one week later, headlines confirmed that the city-based fisheries patrol vessel HMCS Thiepval had foundered with all hands off the Queen Charlotte Islands (Haida Gwaii). Almost all of the 26 aboard were from Victoria.

On the night of Nov. 11, 1918—Armistice Day—the CPR’s Princess Alice returned to Vancouver with the bodies of 137 victims of Sophia on her decks.

The Maritime Museum of British Columbia marked the 100th anniversary of the province’s worst maritime disaster earlier this year. The exhibit included “artefacts and archival documents from multiple organizations for the first time since being salvaged from the wreck…

–Courtesy of Canadian Pacific

A tragic story known I’m my family a long time, as it was very personal. My paternal grandmother was the wife of Captain Locke.

Shipwrecks, alas, were a fact of life in B.C. the so-called “good old days.” One of the reasons I worry at the thought of super tankers in our waters.