PHOENIX, BRITISH COLUMBIA: ‘MILE HIGH CITY’ BUILT ON COPPER

From an area of just two square miles, in a single generation, the Phoenix mines yielded $100 million in copper, gold and silver ores.

Phoenix, British Columbia, “was a camp that for several years at least shipped more ore than all other mining camps of Canada combined; a camp whose principal mine was opened by a man [virtually] broke, but in a few years paid $10 million in dividends; a camp that…started professional hockey in the province…[and the camp] which originated skiing in British Columbia…”

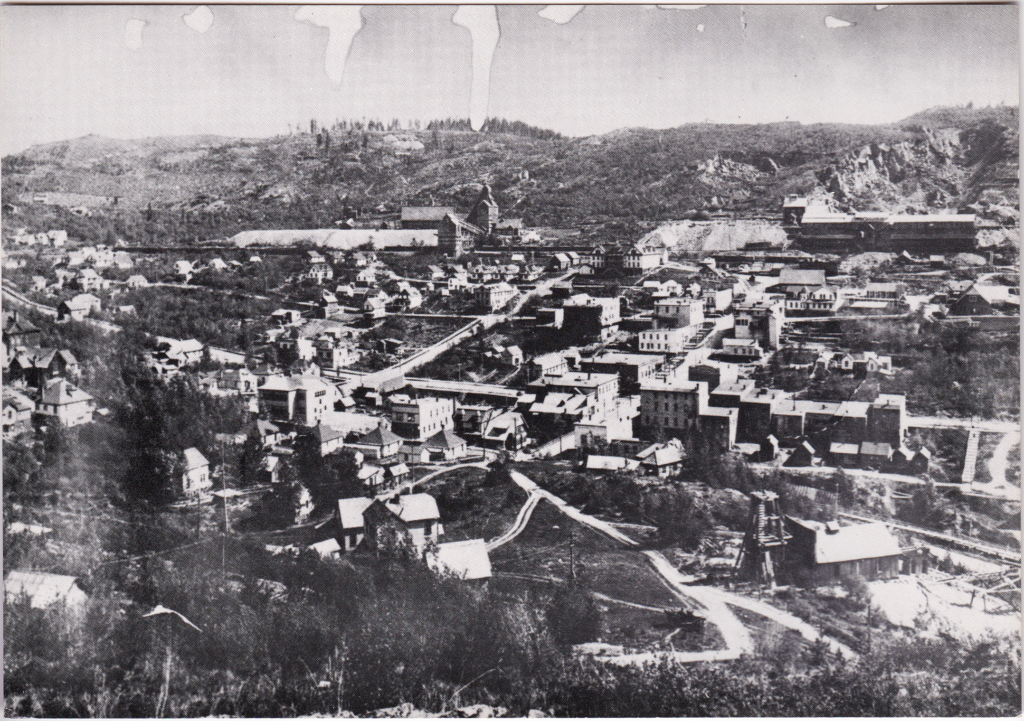

The pioneer “camp” of these impressive distinctions was Phoenix, in its day the “highest incorporated city in Canada.” Like its legendary namesake, it flourished then died—not in flames, to be born anew, but in a whimper, the victim of cold, hard business logic.

Situated in the Boundary District, 20 miles north of the international border at an elevation of 4700 feet (1450m), Phoenix was built on a mountain of copper. After the placer strikes on the Fraser and in the Cariboo, prospectors had poured into the Boundary District. With the discovery of lode deposits at Midway and Greenwood, however, came the realization that gold was greatly surpassed in quantity by deposits of copper which required large-scale production.

Despite the need for a railway, Matthew Hotter and Henry White staked the Old Ironsides and Knob Hill gold claims in July 1891, James Schofield and James Atwood locating the Stemwinder, and Joe Taylor and S. Mangott staking the Brooklyn property.

Three years later John Stevens located the Victoria claim. In the meantime the Silver King, which adjoined the Old Ironsides, had been allowed to lapse and was relocated by Robert Denzler, who named it the Phoenix. It, the Ironsides, Knob Hill, Victoria and Phoenix properties—when mined for their copper—would be the richest of them all and the physical and financial foundation upon which the city of Phoenix would be built.

Vast reserves of copper and construction of the Spokane Falls and Northern Railroad to Marcus, Wa., 60 miles to the south, attracted the Granby Consolidated Mining, Smelting and Power Co. Ltd. The Canadian Pacific Railway soon followed with a 25-mile-long spur between Phoenix and Greenwood, at the base of the mountain, which was completed “amid the shrieking of steam whistles and the cheers of assembled miners and other citizens of Phoenix,” and explosions of dynamite, on May 21, 1900.

By this time, Midway writer Susan Hilliard noted, the ladies of Phoenix “were delicately holding up their skirts as they crossed from boardwalk to boardwalk on dusty Old Ironsides Avenue… ‘Finest wines, liquor and cigars’ were offered at the Brooklyn (the town’s leading hotel), at the Bellevue, the Mint, the Union, the Imperial (table board seven dollars a week), at the Morden, the Maple Leaf, the Butte, the Cottage, Black’s… The Phoenix Pioneer was appearing weekly, and in its mining articles, social notes, and advertisements it struck a note of exuberant optimism…”

Phoenix had four churches, a hospital, school, three-storey theatre, banquet hall and what was said to be the finest ballroom in the interior of the province, besides the usual business establishments and services, a brewery and a covered skating and curling rink.

First Mayor George Rumberger, who’d christened the town in honour of Denzler’s claim, crowed: “The [1900] shipments from Phoenix alone far exceed the combined output of all other mining camps in B.C., outside of Rossland. Yet Phoenix is only in its earliest infancy.”

That July, the CPR had linked Phoenix and Grand Forks by rail, soon followed by the Great Northern. Between 1909 and 1911 Phoenix shipped about 7000 tons of ore daily—half of all the crude copper ore mined in Canada.

But already there were doubts as to its long-term future. Faced with decreasing ore values and with having to update its Grand Forks smelter, Granby Co. looked to its new properties at Anyox in the Portland Canal area, and Granby, on Vancouver Island.

The First World War gave Phoenix a reprieve when copper soared from 11 cents a pound to 28. Upon its fall back to 14 cents, and even as Granby Co. weighed its options, a strike at Fernie closed the coke ovens and idled the Grand Forks, Greenwood and Boundary Falls smelters for months; it was the fatal straw.

Near total demolition immediately followed. Even as residents packed their belongings, salvage crews were razing buildings and tearing up tracks. City council, in one of its last official acts, dedicated money from the sale of the skating rink, which had been paid for by public subscription, to erection and maintenance of a cenotaph in memory of Phoenix’ 14 war dead.

Longtime resident Adolph Cirque, popularly known as “Forepaw” because of a crude iron hook and braces he wore after losing most of an arm, was issued a billy-club and a home-made star cut from a tomato tin, and appointed town watchman for a year, by which time the last residents would have left.

After abandoned homes and buildings were salvaged by neighbouring communities only collapsing mine shafts, rusting fire hydrants, rubble, the cemetery and cenotaph remained. To his dying day, Forepaw remained convinced that “Some day concentrators will be put up and the ore hauled out by trucks, or shot down a tramway to Greenwood.”

He was partially right. In the 1956 the old townsite became the site of a massive open-pit mine which, allowed to flood upon abandonment, became a lake. The cenotaph remains, however, having been moved to higher ground.

In 1999, as part of the City of Greenwood’s 102nd birthday celebrations, a new grave-marker was dedicated for carpenter W.H. Bambury, who remained as Phoenix’ last official resident for a further 30 years after it vanished. Money for the marker came from the a $100,000 profit from the sale of old mine slag.

Among the more colourful Phoenix citizens was six-foot, 10-inch police magistrate W.R. Williams whose unorthodox judicial decisions made him legendary. Once chided by an army officer for not having recognized his rank, Williams haughtily retorted: “Judge Williams, if you please; I want you to understand that I am the highest judge of the highest court in the highest city in Canada.”

Money for W.H. Bambury’s grave-marker in Phoenix did not come from the sale of old mine slag. The money for Mr. Bambury’s grave marker and the idea to put a marker came from the Greenwood Heritage Society of Greenwood, BC and Murray Forbes of the Grand Forks Funeral Home did the installation.

Thank you for the correction, Doreen. I would never intentionally deny giving credit to any B.C. historical society–they’re the backbones of our history. –TW

Thank you Mr. Paterson for your quick reply. I checked our museum records and the contributors for Mr. Bambury’s grave marker were: the Greenwood Heritage Society (Museum), Dode & Marge MacLean, and Leroy Toews of the Toews Funeral Home in Grand Forks.

Thanks again.

Regards,

Doreen