Remembrance: 75 Years Since Second World War

I grew up on the Second World War. On a street like Brett Avenue in Saanich, where every able-bodied father but one served in uniform, playing war was as natural to us kids as playing cowboys and Indians.

And there was no question as to who were the good guys and who were the bad.

We took turns wearing ‘Big Gordie’s’ army helmet. When, in my teens, I last saw it, it was lying in the bushes in the vacant lot across from my home, half-filled with dirt and moss and rusting away.

Come to think of it, the last time I saw Big Gordie’s battle tunic, it was being used for a dog’s blanket. So much for one man’s—and a neighbourhood of kids’—long-term sentiment for war, I guess.

Which isn’t to say the world had turned its back on conflict, however. The Cold War cast its shadow over my childhood, although I was too young to understand, even when we were being taught about the horrors of radiation and having air raid drills, in which we’d all file out of the school in perfect order and assemble on the playground. To this day I haven’t figured out what our next step would have been had there really been an attack.

If air raid practice was disturbing, there was a distinct plus to war games for a lad growing up in post-war, Cold War Victoria. Naval ships regularly conducted gunnery practice in Juan de Fuca Strait and I came to enjoy the anti-aircraft fire that sounded like repeated thunder, particularly on days where there was low cloud cover and the gunfire reverberated between sea and sky—Ka boom—Ka boom—Ka boom!—rattling windows and teacups. Disconcerting though it and air raid sirens during drills must have been to moms who remembered all too well the news reels of the London blitz, to a small boy it was little short of wonderful.

It was even better when an RCAF bomber, with four perfectly purring engines, would skirt the city as it towed an air-filled balloon behind it so that army and coastal gunners could practice their firing. Ka boom! Ka boom!

Now that was real drama for a youngster whose only exposure to war was comic books, movies and magazines. Not until my teens would I really begin to learn something of Canada’s extraordinary war effort. Not until well into my writing career would I ask my own father, William Paterson, of his experiences in the Royal Canadian Navy.

Oh, I knew he’d served in convoy duty in the North Atlantic. He had, after all, run away from home in Medicine Hat, AB at the age of 16 to enlist as a ‘boy seaman,’ so he’d gone through the war from 1939 to 1945. He finished his 20-year hitch as CPO1 (Chief Petty Officer First Class), Electrical and Torpedo, and upon “retiring” from the navy at the golden age of 36, he’d given me his kit. I lost some of it when very young but, fortunately, still have his medals and photo albums and they started me on a lifetime of collecting RCN and naval memorabilia.

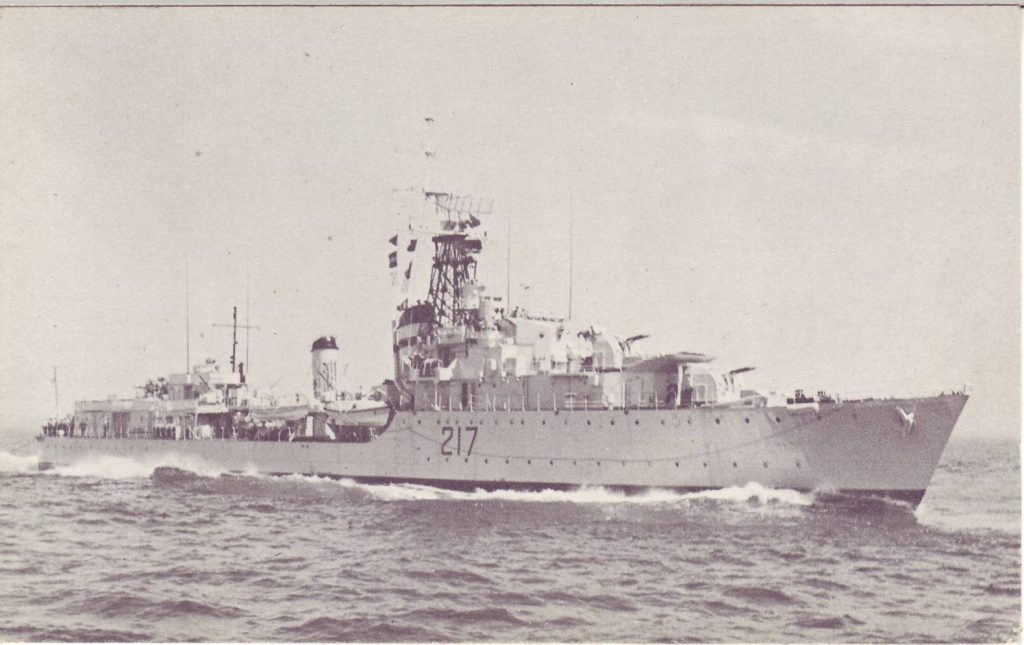

We finally sat at the kitchen table one afternoon, only the quiet hum of my tape recorder accompanying my father’s voice. He began hesitantly, shyly even, his eyes fixed on the microphone although there were just the two of us, father and son. I had to prime him with questions at first. He told me of the ships on which he’d served: HMCS Armentieres, Vancouver, St. Laurent, Skeena, Saguenay, Restigouche and Ontario.

He told of the Skeena stopping in mid-Atlantic to rescue survivors, many of them internees and prisoners-of-war, from the torpedoed liner Arandora Star, of escorting a rescued U-boat captain at gunpoint to the boiler room for safekeeping, of men made unrecognizable by their coatings of oil and, God help them, their burns.

He recalled a long-distance duel between his destroyer and a German tank on a cliff overlooking Dunkirk. He spoke of friends in the service, many of whom joined after war broke out, who were lost. He recounted his last long look at a distant Victoria from the deck of his ship as she sped southward to make it through the Panama Canal before Canada declared war on Germany and her Italian ally. He spoke occasionally of good times—they had them, even in wartime—of comradeship, beer, Captain Morgan rum and cokes, and frozen Halifax.

(Long after the navy and Halifax he maintained some of these friendships; he no longer drank beer but continued to enjoy his rum, always Captain Morgan, and coke.)

He responded to my questions without dramatic flair, almost in a whisper at times, sometimes matter-of-factly. He’d been, after all, a professional seaman. It was his job. As it was for hundreds of thousands of other Canadian men and women who put their lives on the line for King and Country.

Men and women who, like my father, gave up as much as six years of their lives to defend democracy and the way of life that most of us accept as our due.

Normally these thoughts come to me around Battle of the Atlantic and Remembrance Days. But this year’s 75th anniversary of the end of the Second World War with V-J Day, Japan’s surrender, is more special. How ironic that, thanks to COVID-19, there will be no public gatherings at Cenotaphs this year.

That said, Remembrance Day is that in name only to me as I practise ‘Remembrance’ year-round. As the first of three generations of my family who didn’t have to go to war, I owe.

As does every other Canadian who, whether they acknowledge the fact or not, enjoy the benefits of their parents’ and grandparents’ sacrifices.

Cenotaph ceremony or no, may we always remember, not just the fallen, but those who made it home, some of them wounded within, to pick up their lives as husbands and wives and fathers and mothers, and as patriotic citizens who earned their memories and their scars on our behalf.

No Comments

Trackbacks/Pingbacks