The Missionary and the Madman

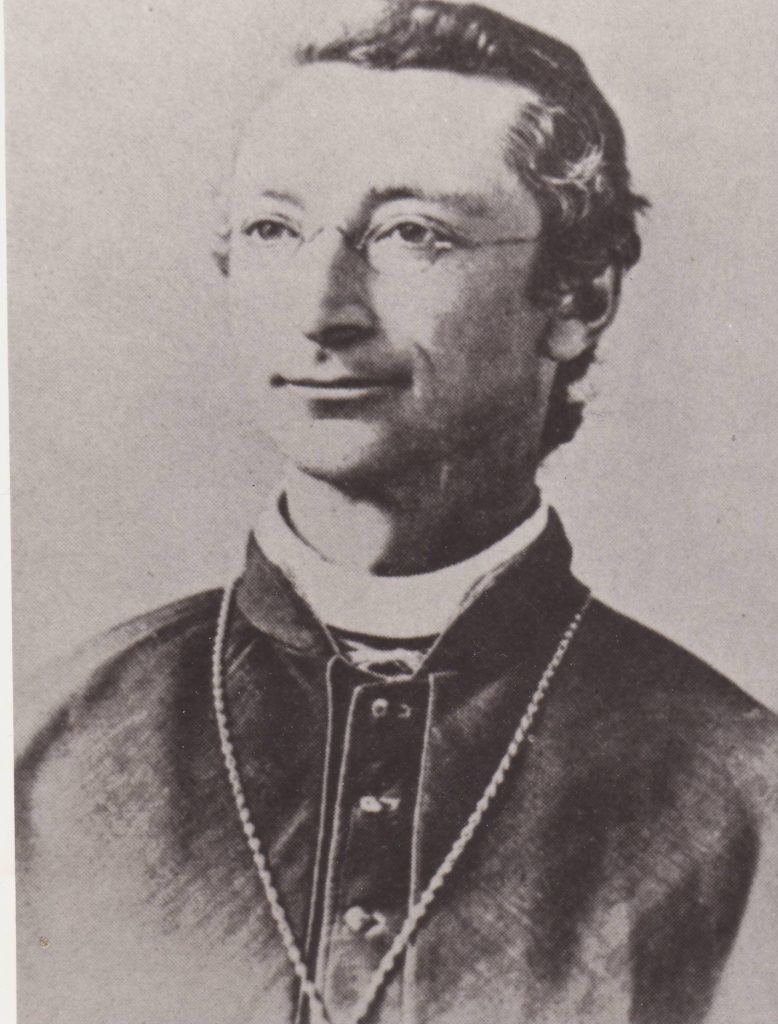

Few men could have been more unalike than Archbishop Charles John Seghers and murderer Francis Fuller.

Archbishop Charles Seghers was dedicated, dignified and fired with the confidence of a noble cause.

Francis Fuller, brooding Irish immigrant, farmer, watchmaker and frustrated layman was consumed by a very different fire—that of the damned.

Born in Ghent, Belgium, Charles John Seghers studied for the missions of far-western America, arriving in the promised land of unsaved souls in 1873 to assume the duties of first Bishop of Vancouver Island.

Despite a near-fatal illness, the man who was fated to become the northwest’s sole “martyr” soon undertook the strenuous task of visiting every portion of his far-flung diocese, which included Alaska, then a gruelling inspection tour by Indian canoe of the west coast of Vancouver Island.

After serving for a time as Archbishop of Oregon, Seghers returned to Victoria as Archbishop of Vancouver Island. He caused a stir when his new archiepiscopal residence cost the then-stupendous sum of $25,000, and was said to be “the most substantial, the handsomest and the costliest” in Victoria.

Citizens were further perplexed when the new archbishop announced his intention to forsake these luxurious quarters to serve as a missionary in the wilds of Yukon and Alaska.

“Adieu! I leave for Alaska and God knows when or whether I shall return. Pray for me.”

And on that curiously haunting note, Archbishop Charles Seghers bade farewell to Victoria. His return, more than two years later, would be in a coffin.

Just months after his departure, a black bordered Victoria Colonist reported that he’d been murdered the previous November by a member of his own party, Brother Fuller, who “is believed to be demented”.

The first to rise one morning, Fuller gathered kindling for a fire but sat down opposite the sleeping Seghers without lighting it. One of their packers heard him say, “Bishop, get up.” As Seghers raised his head and half rose, he found himself staring into the muzzle of Fuller’s gun. At that moment Fuller fired and the bishop “clasped his arms across his breast and bowed his hand. The bullet struck him squarely on the forehead and he never spoke. The muzzle was so close to him that his face was powder-burned.”

The events leading up to his murder had begun earlier, in Oregon City.

That’s where Charles Seghers had formally decided to resume his work as a missionary in Alaska. For companions he was to have Fathers Pascal Tosi and Aloysius Robaut, and the layman assistant who was to be his nemesis, Frank Fuller. Ironically, but for Seghers’ insistence, Fuller would not have accompanied the group as the other Jesuits opposed his inclusion.

A glance at his record since he’d emigrated from the Emerald Isle several years before explains their concerns for the postulant who taught and served as a handyman for his room and board. He was ambitious, intelligent and capable and he initially made a favourable impression upon the Jesuits, only to have to leave the Coeur d’Alene mission under a cloud.

It became a pattern: serve as layman helper, become immediately popular, then have the amicable relationship collapse because he was overtly suspicious of all about him.

He’d begged Seghers to take him to Alaska as general factotum and, impressed with his spirit, the open hearted archbishop had consented. When Father Tosi and others argued against his decision, Seghers refused to heed them.

Friction between Fuller and the other priests developed immediately.

Throughout their northward voyage, Father Tosi remarked in a letter, Fuller was irascible and surly, suspicious of their every move, and convinced that someone was plotting to kill him. He took to carrying a revolver, which Tosi confiscated. With every utterance and action, Fuller convinced Tosi that he was not only unfit to accompany them but dangerous.

All the while, Fuller attended to the archbishop’s every need, even carrying his pack on the trail, thereby convincing the naive Seghers that Tosi and Robaut were exaggerating their differences with Fuller. Despite their protests, Charles Seghers continued to think highly of his helper.

They pushed on, not a day passing without friction between Fuller and the two priests, while Seghers remained aloof from the bickering. After a further month of hardships and antipathy, Tosi and Robaut refused to accompany them on to Nulato until the spring.

When, five months later, the rested priests started down the Yukon by steamer, they were appalled to hear that Archbishop Charles Seghers had been slain by Frank Fuller.

From the testimony of the natives who’d accompanied the archbishop and his assistant, it became apparent that the isolation and exhaustion of their hectic march in worsening weather had snapped Fuller’s already unbalanced mind. Statements he later made to authorities showed that his persecution complex had rendered him mad. But days from their objective, Fuller had grabbed up his rifle and shot the unsuspecting bishop.

Immediately after the slaying he’d seemed to be relieved of a great burden and at peace with himself. But he would awaken during the night, screaming that he had to push on to Nulato.

When he faced trial in Sitka a full year after Archbishop Charles Seghers’ murder, a baffled jury returned a verdict of manslaughter, for which he received a sentence of 10 years’ hard labour and $1,000 fine.

U.S. Marshal Atkins, who escorted him to prison, told reporters that Fuller “is what I would call a religious crank… He comforts himself with the belief that the Lord bade him to commit the deed.”

After serving eight years Fuller was released for good behaviour. Some years after, during a violent argument, he was shot dead in self defence.

When Archbishop Charles Seghers’ and Francis Fuller’s destinies collided, one had to die.

See Also: Archbishop Charles John Seghers, Wikipedia