The Mystery of Johanna Maguire

“Had I been asked to point to a thoroughly depraved and worthless person I should have indicated the Maguire woman.”–D.W. Higgins

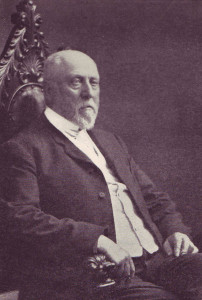

D.W. Higgins

How many fascinating characters have departed the British Columbia stage, unknown and unsung? The answer must be in legions as few have been blessed with recognition let alone immortality.

One who almost slipped through the cracks, as much by design as by circumstance, was the mysterious Johanna Maguire. Fortunately for posterity, she encountered journalist D.W. Higgins at Fort Yale, then a booming gold camp. Higgins was working as agent for the express company that carried mail up and down the Fraser River.

“One morning a tall, dissipated-looking woman, very plainly draped, entered the place and enquired if there were any letters for Johanna Maguire,” Higgins wrote in a series of priceless reminiscences that were published in the Victoria Colonist shortly after the turn of the last century.

There was a letter, bearing a Dublin postmark. She opened it, extracted a five-pound Bank of England note and left to have it changed at the gold commissioner’s office. Weekly thereafter, Johanna appeared at the express office, usually to be rewarded with a five-pound note.

Higgins was intrigued

Her remittance, although generous given the values of the day, wasn’t extraordinary in itself but she intrigued Higgins who had the journalist’s eye and nose for a good story. Common, crude and belligerent, she spurned conversation and always spoke “with a broad Irish accent; there was nothing about her language to indicate that she belonged to other than the peasant or uneducated class.

“Sometimes she would be in a quarrelsome mood, then she would swear like a trooper on the street.”

Twice during drinking binges she’d “worn out a chair on the heads and bodies of some miners who had misbehaved themselves while in her house. She was habitually profane, and it seemed to me she must have sprung from the lowest of the low. Had I been asked to point to a thoroughly depraved and worthless person I should have indicated the Maguire woman…”

Johanna’s character–or lack of it–was none of Higgins’s business, of course, and he likely would have forgotten her had he not been asked to accompany Dr. Max Fifer to the bedside of a 14-year-old girl who was said to be dying of pneumonia in a shack behind Yale proper. The despondent and drunk father sat, sobbing, on the front steps; inside they found the tiny shack partitioned into kitchen and bedroom with a piece of muslin from behind which they could hear a woman reciting the Lord’s Prayer “in a soft, sweet” voice.

“Then there followed a sound as of a woman weeping, in the midst of which Dr. Fifer parted the muslin and entered.”

To Higgins’s astonishment he heard the unmistakably coarse voice of Johanna Maguire, gushing with relief at the doctor’s arrival. Fifer, equally astounded to see her there, demanded to know where the woman of the sweet voice and Lord’s Prayer had gone. “She hopped out of the windy as ye came in,” Johanna replied with a sneer. When Fifer dismissed this as ridiculous, she swore, pushed by him and stomped out.

The girl recovered and moved away and Johanna continued to call for her mail. When there was none she would become profane and have to be ordered away.

One evening, three weeks later, while strolling the riverbank with friend Kelly, an Australian barrister, Higgins heard a woman screaming hysterically. The weather had been warm, the river was high, and uprooted trees were being swept downstream in an endless chain. Johanna Maguire appeared: “There’s a man afloat on a tree. Get a boat!”

Several miners tried to intercept the castaway before he was swept through the rapids downstream but darkness closed before they could reach him. All the while, Higgins’s attention was fixed upon Johanna Maguire, whose anguish over the fate of a stranger was startling–as was the fact that she’d encouraged the rescue effort “with the most perfect English. There was not a trace of the brogue, and her language gave every evidence of good breeding. As her excitement wore off she seemed to recollect herself, and presently she lapsed into the brogue and with an oath in condemnation of the fruitless effort to save,” she returned to her shack.

They meet again in a Victoria courtroom

Higgins told Kelly of having heard Johanna’s clear recitation of the Lord’s Prayer. Both agreed she wasn’t the woman she pretended to be. Then both answered job opportunities in Victoria and Higgins forgot about her. For months he went about his duties as a Colonist reporter, covering the tragic, humorous and wondrous vagaries of human nature which were aired in the old police barracks in Bastion Square.

On a summer morning in 1861 he duly took his seat in the courtroom presided over by Magistrate A.F. Pemberton. To his astonishment, “Who should I see on the bench usually allotted to witnesses but Johanna Maguire. She was “in a fearful state. Her face was battered and bruised, her eyes blackened and she was almost doubled up with bodily stiffness.

“A bloody rag was tied about the lower part of her face, and a more deplorable spectacle it would be hard to imagine.”

Standing in the prisoner’s box was another former acquaintance, Ned Whitney. He, too, appeared to be the worse for wear. When Higgins first met him in San Francisco, Whitney was “a fine, steady fellow,” a graduate of a leading American college and devoted to singing in church choirs. At that time he was “as regular and reliable as a good watch”.

Johanna takes the witness stand

But after joining the rush to the B.C. gold fields he’d fallen in with bad company. Somehow he’d taken up with the Maguire woman on lowly Kanaka Row, then Victoria’s ghetto for down-and-outers. Finally, during a drinking bout, they’d gotten into an argument and Whitney had beaten her black and blue. Hence the appearance of both in Pemberton’s arena, he in the prisoner’s box, she on the bench reserved for witnesses.

While waiting for the trial to begin, Higgins engaged her in conversation. The battered woman responded weakly and without her hostility of old. She said she’d changed her mind, she didn’t wish to press the assault charge against Ned.

Higgins’s friend Kelly, appearing for the defense, was spared having to earn his fee when Johanna addressed the court on Ned’s behalf then paid his small fine. That evening, a note “written in a neat female hand,” requested that Higgins call upon Mrs. Maguire. He found her alone and ill with a high fever and three fractured ribs from another beating and dragged a protesting Dr. Trimble to her bedside.

Convinced that she was dying, Johanna sent for lawyer Kelly. To him she hinted at the personal tragedy that had brought her to a shack in Victoria, half a world from home, and gave Kelly letters and some jewellery to be sent to a Dublin address upon her death.

But Johanna didn’t die

Upon recovery she demanded the return of her effects and sailed for San Francisco. Neither Higgins nor Kelly saw her again and it was 40 years later that Higgins pondered her true identity. Kelly, long dead, had said only that she’d been “a welcome visitor at Dublin Castle and that she was connected with one of the highest families in Dublin, a family with an historical record and a lineage that dated back several centuries. He also told me her brogue and rude manners were assumed to conceal her identity, and that she was really a cultivated woman who had had superior advantages in her youth.”

Her monthly remittance had been to keep her in exile. Once, she told Kelly, she’d met an old family friend in B.C. who, to her immense relief, failed to recognize the profane, disheveled woman before him.

* * *

In recent years a family physician researching the biography of Yale’s Dr. Maximilian W. Fifer came to quite a different conclusion: that Johanna Maguire’s outbursts of temper and profanity hadn’t been an act, but had been involuntary because she suffered from Tourette’s Syndrome.

I prefer D.W. Higgins’s theory myself.

Update:

The story told above is taken directly from the reminiscence of D.W. Higgins, back to his true calling as a journalist in Victoria at the time of Johanna’s brutal beating from which she’d recovered. So wrote Higgins. But there’s a problem.

While recently researching the Leech River gold rush in the 1864 British Colonist, I came upon a news account of Whitney’s brutal assault which the editor referred to as, “savage inhumanity…cruel…cowardly”. According to this report, Johanna had been rushed to the hospital in “a very precarious condition”.

Three days later, the Colonist reported her death “despite every possible attention shown her by the attending physicians”. She hadn’t gone easily, having “raved very much…and required close watching”.

At the inquest, held next day,

Landlord William Seely testified to having found her, weeks before, with blackened eyes and bloodied. He’d called for a policeman who’d said he could do nothing without evidence but declared, with Whitney present, that if he knew who was responsible, “the man would not live till the morning”. Johanna was unable to speak.

It was Seely who found her unconscious the second time and who again called for the police and a doctor. Johanna was unconscious, Whitney lying on the bed beside her.

A fellow boarder told how he’d heard scuffling from the adjoining room and had previously seen evidence of her having been beaten but he’d minded his own business. He’d never seen anyone other than Whitney in their room. As for Whitney, when dispatched for a doctor, he’d returned instead with a bottle of gin.

Last to take the stand was Dr. Trimble

He’d attended her at the end. She was very drunk. After describing her various wounds, he said that he’d asked her, not once but several times, who’d hurt her, and she’d replied, “it was herself”.

His post-mortem examination revealed her physical injuries to have been superficial; internally, however, she was in a very advanced state of deterioration from years of alcohol abuse, her liver weighing more than twice its normal weight. In fact, he’d “never [seen] the organs of any person generally so unhealthy; any shock to the system in the condition in which the woman was [in] might produce death”.

He attributed death to apoplexy; “I could not see anything externally to warrant my stating that death was accelerated by personal violence… I believe a course of intemperance brought her to the diseased condition in which I found her.”

Suffice to say, this was good news for Whitney. It took the jury but a few minutes to rule that Johanna Maguire died, not from a brutal beating, but from “an effusion of blood to the brain,” and he was released.

Just wondering what family in Ireland was joahanna from?

Now that’s the mystery of Johanna Maguire, isn’t it. Sometimes, mysteries are better unsolved, don’t you think? Certainly they make for a better story! TW

Thanks for another fantastic article. Where else could anybody

get that type of information in such an ideal means

of writing? I’ve a presentation next week, and I am on the look for such

info. http://tools.hackerjournals.com/?p=10883,Canada Goose Parka

Excellent blog here! Also your web site loads up fast!

What web host are you using? Can I get your

affiliate link to your host? I wish my web site loaded

up as fast as yours lol

I’m truly enjoying the design and layout of your site. It’s a very easy on the eyes which

makes it much more enjoyable for me to come here and visit more often.

Did you hire out a developer to create your theme? Superb work!

Also visit my blog post; http://www.iamsport.org/pg/blog/party57953/read/24265304/how-to-use-a-ba…

Merci, Ivan. Please keep reading; lots more to come. –TWP

I’ve been absent for some time, but now I remember why I use to love this site.

Thank you, I will try and chedk back more frequently.

How frequently you update your website?

Hi Julia: For various reasons I’ve had to neglect my site for some time now. I’m trying to get back to blogging regularly (I have content up to my ears!) asap. Believe me, I’m trying……………………!!!! Thank you for your interest. –TW