The Outrageous Francis O’Bierne Alienated All Who Knew Him

To those unfortunate enough to have known the outrageous Francis O’Bierne personally, he was just “Mr. O’B.”—or worse.

For many years (perhaps mercifully) his real identity was a mystery. Not until CBC actor and writer Tommy Tweed did some historical sleuthing in the 1970s was the cantankerous Francis O’Bierne’s identity revealed.

Tweed’s interest in this son of a bishop and student (if not graduate) of Cambridge, was because of Francis O’Bierne’s dubious role in provincial history–as one of the most annoying, obnoxious and exasperating individuals ever to set foot on the B.C. stage.

In light of later events, it’s easy to see why so little was known of O’Bierne’s background.

Family and friends must have made every effort to forget him. It is record that one of the first controversies in which he became involved was his conversion to ‘free thinker’ after his expulsion from a Catholic school. For almost a decade, he made a career of touring England, lecturing upon the evils of Catholicism.

Francis O’Bierne also acquired other passions during this period: travel and liquor (not necessarily in that order). The former kept him on the move for the rest of his life; the latter not only shortened his blemished career, but destroyed whatever potential he may have had and cost him the friendship and respect of those whom he met.

“By the late 1850s,” wrote the late Harold Fryer in Alberta: The Pioneer Years, “we find him in the United States where he had strayed after serving some time as a journalist in India. He was working as secretary to a wealthy Louisiana planter when the American Civil War broke out. Appointed to the Home Guard with the rank of captain, Mr. O’B. envisioned flashing swords and bayonets, all directed at various parts of his anatomy, and promptly fled northward to Canada where, in 1861, he showed up at the Red River Colony in Manitoba…”

Francis O’Bierne’s arrival in the colony was not the settlers’ gain and, thanks to his preference for bending his elbow over any other form of exertion, he soon wore out his welcome.

–Glenbow Foundation Library

With the cold suggestion, in the spring of ‘62, that he move on, Mr. O’B.’s future looked grim.

As luck would have it, a party of the famous Overlanders passed through Manitoba on their way to the British Columbia gold fields. Francis O’Bierne, never deaf to the golden knock of opportunity, persuaded the leaders of the group of 150 men, women and children that they needed a veteran traveler such as he to accompany them as they struck westward across the prairies at a speed of 2 ½ miles an hour by oxcart. Then it was over the Rockies and down the Fraser and Thompson rivers. Remarkably, most made it, although some were lost when their rafts were upset in river rapids.

All of this had proved to be much too heroic for Francis O’Bierne, who’d been rudely abandoned at Fort Carlton. Before long, that welcome mat was withdrawn and the friendless wanderer was forced to move upriver to the Smoky Lake mission of Wesleyan missionary Thomas Woolsey. It was there that the Rev. John McDougal met O’Bierne whom he later described as an “old wandering Jew kind of man, one of those human beings who seem to be trying to hide from themselves…”

O’Bierne had been evicted from Fort Edmonton, McDougal wrote, because of a rule by Governor Dallas that “no Hudson’s Bay officer should allow stragglers to stay around the posts. The fine for doing so was 10 shillings a day per stranger.”

Moved by pity, the Rev. Woolsey had invited O’B. to stay with him until arrangements could be made for him to move on. McDougal knew Francis O’Bierne to be well-educated and was quick to note his addiction to “the liquor curse.

“His was another life blasted by the demon from the bottomless pit.”

O’Bierne’s craze for drink had provided a pathetic yet humorous moment when, rummaging about the mission, he found a keg which once had contained liquor. McDougal saw him lift it to his nose, inhale hopefully then, with a smile of anticipation, fill the keg with water. Over succeeding days, the missionary watched as he anxiously visited the cask, shook it eagerly and took a deep whiff before returning it to its hiding place.

Finally, after several such ceremonies, McDougal heard him mutter to himself, “It is getting good.”

Alas, the missionary showed something of a sadistic streak when he wrote in his memoirs that he thought he would “make it better. I secretly took the keg, emptied it and filled it with fresh water. Mr. O’B took great pleasure in drinking this, though the taste must have become very faint indeed!”

In the spring of 1863, when even the good natured Rev. Thomas Woolsey, tired of him, he took the Rev. McDougal aside and asked that he take O’B. to Fort Edmonton where he’d already worn out his welcome.

McDougal immediately regretted allowing the 52-year-old derelict to accompany him.

Francis O’Bierne insisted upon riding rather than walking behind the sled; time and again his extra weight proved almost disastrous for the dogs as they struggled to make headway across the river ice. Forced to swim, the burden of sled and passenger almost pulled them under.

When the cariole began to ship water O’B. would blame McDougal “and presently began to curse me roundly, declaring I was doing it on purpose. All this time I was wading in the water and keeping the sled from upsetting.” His un-Christian response was to tip his shocked passenger onto the ice.

O’B. continued to be obnoxious. Beside the river as they approached the fort, McDougal deliberately let the sled almost capsize. As O’B. blustered and swore, the hard hearted missionary “slackened the line a little [and] let the sled flop up and down in the current and finally accepted his apology on condition that he would behave himself in the future…”

By pure luck, two travellers came to McDougal’s rescue.

Such certainly wasn’t the intention of Viscount Milton or Dr. W.B. Cheadle who were seeking a passable route through the Rockies to British Columbia. Reluctantly, they succumbed to his pleas of having to continually fight off grizzly bears and wolves from his cabin, a quarter of a mile outside the fort.

The penniless O’B. soon appeared with a complete outfit of horse, blankets and 40 pounds of pemmican. Upon its being announced that he was to accompany the Milton-Cheadle expedition, Edmontonians had passed the hat, most making very generous donations of one pound sterling each. One relieved inhabitant even contributed two pounds!

“It was a motley crew that left Edmonton the second week in June,” wrote Harold Fryer wrote in Alberta: The Pioneer Years. Besides Milton, Cheadle and O’Bierne there were Louis Batenotte, his wife and young son and a guide, with 12 pack and saddle horses.

Mr. O’B. immediately set the tone when he accused Batenotte of “every crime in the book, including murder”. Then O’Bierne refused to pack his own horse and even required help to roll his blankets…”

O’Bierne often fell so far behind that he’d lose his way; then he’d seat himself comfortably on a stump or log and wait until someone came back for him. Batenotte soon tired of this and, on the third day, hid beside the trail. When the straggler came abreast of his hiding place, he, well aware of O’B.’s near-paranoia of grizzlies, growled and beat the bushes.

The terrified O’Bierne spurred his horse forward and didn’t stop until he caught up with his comrades.

Beyond Lac Ste. Anne, the trail disappeared and they had to battle jungle-like growth, blackflies and mosquitoes. These pests became doubly hazardous when a horse kicked over a smudge-pot, sparking a brush fire. All fought the flames with axes and blankets–O’B. manfully attacking the flames with the contents of his teacup.

Their next hazard was water. Forced to build rafts to descend the Athabasca River to Jasper House, they felled trees, All except Francis O’Bierne, who slipped away. A miffed Milton, upon finding him seated on a log, smoking his pipe and reading his only true companion, Paley’s Evidence of Christianity, asked him if he’d mind helping him carry a log?

O’B. grabbed the tapered end, thereby leaving the heavier load to Milton, then complained bitterly that the log was injuring his shoulder. At the riverbank, he let go without warning, his end of the log striking the ground with such force that the concussion almost knocked Milton off his feet.

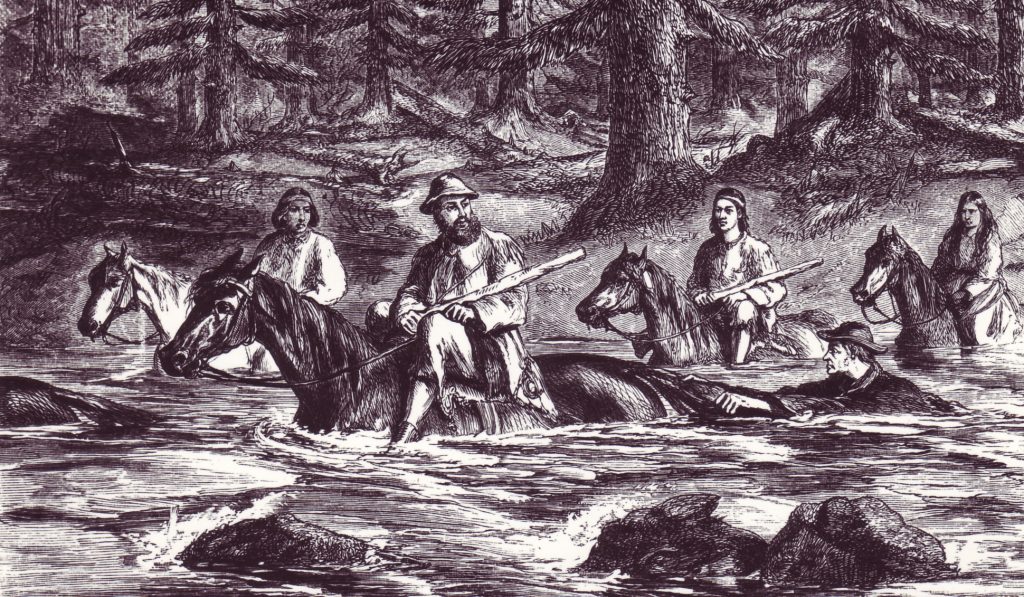

That same day, while leading his horse across the river, O’B. lost his footing, his horse and his nerve. He headed for deeper water and was in the act of drowning when Milton (against his better judgment) rescued him. Thereafter, O’Bierne let his horse pull him across as he held on by its tail.

Finally, on August 28, 1863, the exhausted party stumbled into Fort Kamloops after losing much of their outfit and several pack horses to the Fraser River. Milton and Cheadle saw the last of their sorry companion when Francis O’Bierne proceeded to Victoria alone.

Did he finally find peace, if not fame and fortune, there? “Not so you would notice,” wrote Fryer.” For a while he was employed as a church secretary” before moving on to San Francisco, Australia and New Zealand where the trail ends.

Perhaps Eugene Francis O’Bierne—the outrageous Mr. O’B.—is still wandering up yonder, seeking God only knows what and burning his bridges as he goes.

One of the original “Homeless” people who wore out his welcome wherever he traveled.

Indeed!!