Cumberland’s Chinatown gone but not forgotten

The locals laughed when American collectors began hauling away bottles by the truckload…

Here’s irony for you. Fifty years after collectors razed Chinatown to the ground in search of bottles, pottery and curios, the Village of Cumberland is out to recreate some of its Asian heritage with Coal Creek Historic Park.

According to Drew Penner in the Comox Valley Echo, “The 40-hectare property containing Chinatown and No. 1 Japanese Town was given to the Village of Cumberland by Weldwood Canada in 2002, with the stipulation that a covenant be put in place to protect its heritage and ecology.”

Talk about locking the barn door after the horse has bolted!

Let me put it this way, with a column I wrote in the Cowichan Valley Citizen in 2002:

Although it’s now a matter of history, Cumberland’s Chinatown lives on in the form of thousands of collectibles dug from its swampy soil before the historic community succumbed to the onslaught of age, neglect, vandals, bottle diggers and bulldozers.

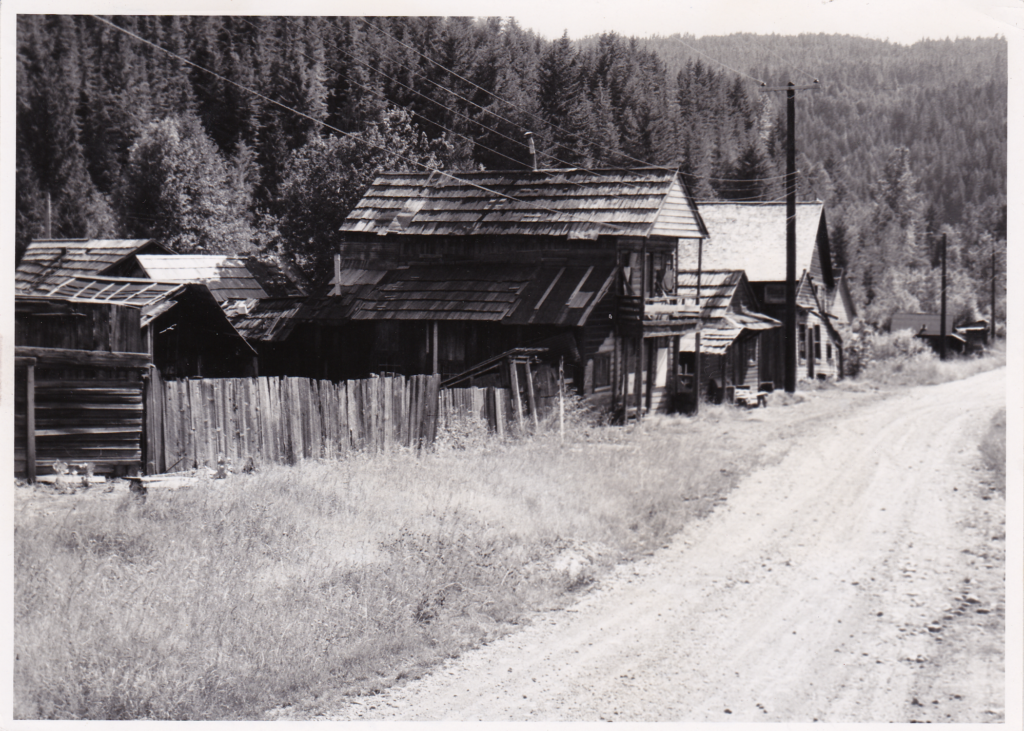

Once its 3000 residents made it the second largest such community outside of San Francisco. By the 1960s, when it became a destination dig for Canadian and American bottle collectors, most of its buildings had succumbed to fire and recyclers. Only a few survivors were occupied by a handful of residents. The most imposing of these was the two-storey casino, built on pilings and steadily sinking into the swamp at the time of its demolition.

Collectors came from as far as Vermont

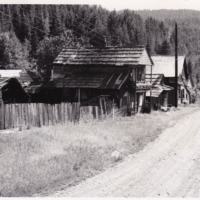

Vandals and bottle diggers (sometimes, alas, they’re one and the same) have begun their work on this former Chinese miner’s humble home.

Some cabins were still occupied in the mid-’60s.

Bottle diggers soon transformed the townsite into a battlefield of holes and trenches, uprooted trees, pillaged houses and discarded rubble. Because the land had been reclaimed from the swamp with ashes from decades of wood-burning stoves, most of these excavations filled with water.

Gone by this time were the dubiously named ‘Jap’ and ‘Coon’ towns whose locations revealed the racial pecking order of the times: Whites had the high ground, blacks the middle ground, Japanese the forest fringes, and the maligned but essential Chinese miners the swamp.

This segregation revealed itself in the unearthing of hundreds of bottles which had contained expensive liquors of many nationalities–indicating that the Chinese preferred to import such luxuries rather than patronize the local merchants.

Today’s visitors have even greater difficulty imagining that this was a bustling community because the landscape has recovered from the onslaught of 40 years ago.

The single surviving structure is, ironically, its first and last. Built about 1869, this log cabin reputedly served as coal baron Robert Dunsmuir’s office, the town jail, and for many years as the home of a Chinese resident known as Jumbo. It has been restored, moved and is now an integral part of Cumberland’s aroused historical awareness.

Twenty years ago, there was little to be seen then other than Jumbo’s derelict cabin. But with the help of photos one could pinpoint the locations of many of the homes and buildings, some of which had been occupied until the late ‘60s by the remaining 20-odd residents who’d rented their cabins and former stores for as little as a dollar a year from then-owners, Weldwood Canada.

Friendly but shy as they sat in the sun, they’d chatted with visitors and watched their antics in bemused silence.

Then, like Chinatown itself, they were gone

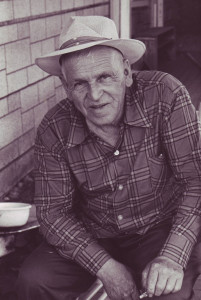

The late Lawrence Schendl whose chickens did the work for him in digging up bottles and crockery on his property.

Retired miner Lawrence Schendl lived just above the townsite. For years, his scratching chickens had unearthed hundreds of old bottles which meant nothing to him or other locals. Then had come the collectors and the dealers and Mr. Schendl had willingly traded his new-born ‘antiques’ for cash. When the townsite was under private lease, he’d served as watchman, gathered a nominal daily fee from visitors, suggested potential treasure sites and regaled his listeners with descriptions of the Chinatown of old.

Unknown thousands of bottles and relics from Cumberland’s Chinatown are now spread across the continent.

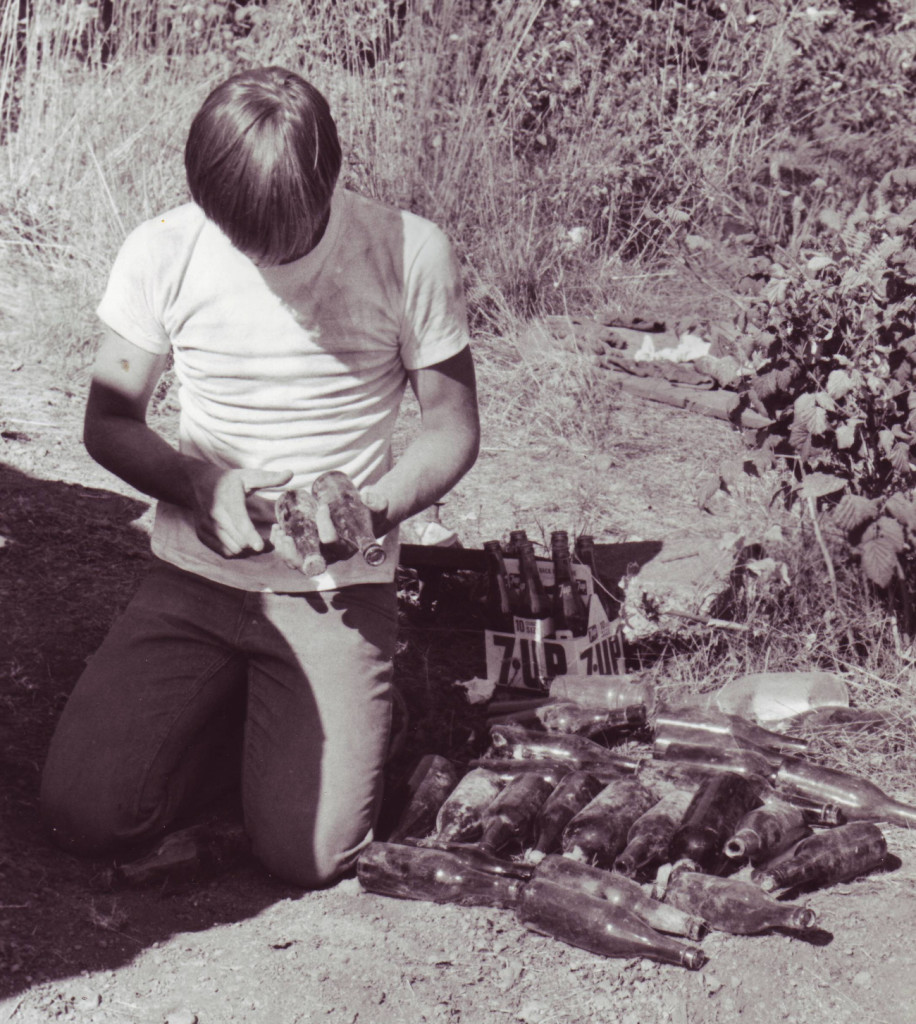

They recall the bygone coal mining era in the Comox Valley, and the Chinese miners who made the most of their free hours with fine wines and liquors and games of chance. ‘Tiger’ whisky crocks and assorted pottery, hand-blown bottles (so crudely done that no two are alike), ‘black glass,’ ‘opium’ (actually medicine) bottles and pipes, brass opium cans and coins, fan tan chips, abalone buttons, and scores of other prized relics have become conversation pieces on bookshelves and coffee tables in hundreds of homes.

Some of the bounty from a day’s work in the hot Cumberland sun. Yes, many of the bottles were plain janes although I’ve always loved Chinese glass and pottery ware for the fact that they were so crudely produced that no two are exactly alike. And their teal blues and greens are truly beautiful.

Few found their way into the Cumberland or B.C. Provincial museums, however, as the former didn’t exist at that time, and Victoria showed no interest in the pit-mining of Chinatown. Duncan’s and Nanaimo’s Chinese communities have vanished, too, the former in the name of progress, the latter by fire.

So I wrote in 2002. The pioneer Chinese, Japanese and white miners and their families still have their own cemeteries but Cumberland now has an excellent and inclusive museum. So it was and so it is.

Progress of sorts, I guess.

See also…Bottle Digger’s lament

I love bottle digging here in the valley including Chinatown

I should think that your area is rich in old bottle dumps from the mining, logging and settler days–if you can find them and if they haven’t been buried under tarmac or there’s a building on top of them. Happy hunting!

But haven’t had any luck in Chinatown it’s just been pillaged through and there’s old big depressions in the ground where you can tell someone dug and there’s billions of them at the casino

I haven’t been back to Cumberland for several years. The last time, perhaps six-seven years ago, was to check out a tip that the city had dumped loads of soil in the Chinatown area that they’d hauled from elsewhere. My informant said there were bottles in the piles and, sure enough, there were.

I remember getting a torpedo seltzer and my companions all found a keeper or two.

The question, of course, was where did the city work crews dig them up?

Right now, here in the Cowichan Valley where I live, most of the woods are off-limits, gated because of the fire hazard. So it’ll be fall before we can hope to get out again.

Another problem is that in so many sites, logging and mining, what we unearth is shattered, sometimes almost pulverized. It’s as if someone ran a Cat over them. Too, it was common practice to burn garbage to discourage bears and rats.

No wonder digging up a good bottle is such a trick these days! –TW

I was there in the early days..late 60’s..1970…..dug lots of great stuff…. once in a lifetime memory

Yes, Cumberland’s Chinatown was a once in a lifetime opportunity. I still dig for bottles but old dump sites of any size are scarce now and it’s been years since Jennifer and I have hit a glory hole. But we’re still hoping and still trying!

Chinese bottles and pottery are my favourites, by the way, for the beautiful teal blue and green glass and the crude pottery. All hand-blown and hand-made, no two are alike! Similar, of course, but not truly identical. This gives them far more character than yoiu can get from a factory mold.