Forest Workers Memorial Park, Lake Cowichan

With everyone’s thoughts on the COVID-19 crisis, this year’s national Workers’ Day of Mourning passed quietly.

For some years now April 28th has been officially designated the annual Day of Mourning to “remember those who have died on the job, and to reflect on what needs to be done to prevent more deaths and injuries”.

Locally, it has become the practice of representatives of various labour councils and others to gather at Forest Workers Memorial Park, the first of its kind in B.C. It’s situated in Lake Cowichan because the Cowichan Lake region has a long history of logging and milling and because it’s where a loggers’ union, the IWA, first took root in the 1920s.

Funded by the sale of Commemorative Bricks, the local Credit Union Legacy Fund and local industry, the small park consists of a fountain, three carved signboards depicting various logging scenes, and a chunk of concrete foundation from the Canadian National Railways bridge that used to span the Cowichan River at this site.

The piece of bridge symbolizes the many logging railways that once worked around the lake; the fountain recognizes the mountains, lakes and rivers in the area; the interpretative panels carved in yellow cedar depict historic events from the forest industry.

Circling the fountain, grey Commemorative Bricks recognize workers and companies past and present. Brown bricks with a tree emblem recognize those workers who were killed on the job.

Each of the Commemorative Bricks has three 15-character lines of type that give the name, appropriate dates and places of employment or death, much like an abbreviated headstone. Here, unlike a regular cemetery, where logging victims are lost in a sea of graves, the prevalence of brown bricks, some remembering quite recent casualties, remind us that workplace fatalities and injuries are a continuing threat to working men and women.

May 26, 2007, the day the park was dedicated, “began with sun in the sky, and a parade of logging trucks from the 1930s, ‘50s and present day. The local Kaatza Museum was open with a series of logging and mining displays. As the park grand opening drew near the heavens opened, the rain poured down, as if to remind all in attendance that forest workers work outdoors in the harshest of elements…”

Originally, this event was held in Duncan, at the United Steelworkers, I-80 headquarters on Brae Road. After the ceremony itself attendees could view a collection of historic photos and logging memorabilia in the basement.

Since moving to Forest Workers Memorial Park, however, Kaatza Historical Museum, just across the road, opens its doors to a public display of some 200 logging and sawmilling photos and archival video footage.

Most of these outstanding photos are the work of the late Youbou photographer Wilmer Gold.

They depict logging as it was in the 1930s and 1940s: steam donkeys, steam locomotives, the first logging trucks, hand-falling with a two-man “misery whip,” camp life and the loggers themselves. Mostly, they’re young and fit looking in their soiled Stanfields and cut-off jeans.

Logging was a he-man’s world—and a dangerous one.

Little in the way of safety gear is shown; bulldozers lack roll bars, and trucks (their driver’s door removed to allow the driver a fast bailout) strain under the weight of monster-sized first-growth logs that are only secured by thin chains. Fibreglass hard hats, apparently optional, appear only in photos from the mid-‘40s on.

Here then is the story of one of the men whose name is on a brown Commemorative Brick in Forest Workers Memorial Park…

* * * * * *

Several years ago, the discovery in Nanaimo of a private family photo collection and a chance dinner conversation resulted in hundreds of family photos “going home” to Tom Teer, the great nephew of a man he’d never met because his life was taken on the job, June 18, 1943.

Walter Hogg, Nanaimo, was 25 and married just a year when he was fatally injured while working as a faller for Piggot & McIntyre, contractors for Hillcrest Logging Co. at their logging operation south of Lake Cowichan.

A brief front-page story in the Cowichan Leader noted that he’d been struck on the head by a falling snag and that he died in Duncan hospital the next day. It was stated that he wasn’t wearing a hardhat at the time and a coroner’s jury brought in a verdict of accidental death with no blame attached.

Previously employed by the Dollar lumber Co., he’d been with Piggott & McIntyre for just a week. Walter Hogg left his widow, Violet, his parents and two older brothers.

When Violet died in April 2006, Virginia and Ian Jones of Everett, Wash., came to Nanaimo to clear up her estate.

They asked city antique dealer Gerald Gonske to appraise some of the larger items. He noticed four boxes of albums and loose photos, mostly of Violet’s family, and some depicting Nanaimo scenes of the previous century. These, he suggested to the Joneses, would be of interest to his friend, Tom Paterson, who was then writing weekly historical columns in the Harbour City Star and the Cowichan Valley Citizen.

With the Joneses’ permission I was allowed to see Violet’s collection. She’d kept almost everything, it seems, including invitations, greeting cards, newspaper clippings that dealt mostly with weddings and deaths of family and friends, and personal correspondence.

Among them was a framed black and white enlargement of a tall, lanky man in soiled work clothes and suspenders, narrow brimmed hardhat, lunchbox under his arm, gloves in hand and a cigarette dangling from his mouth as he stands on a stretch of railway track.

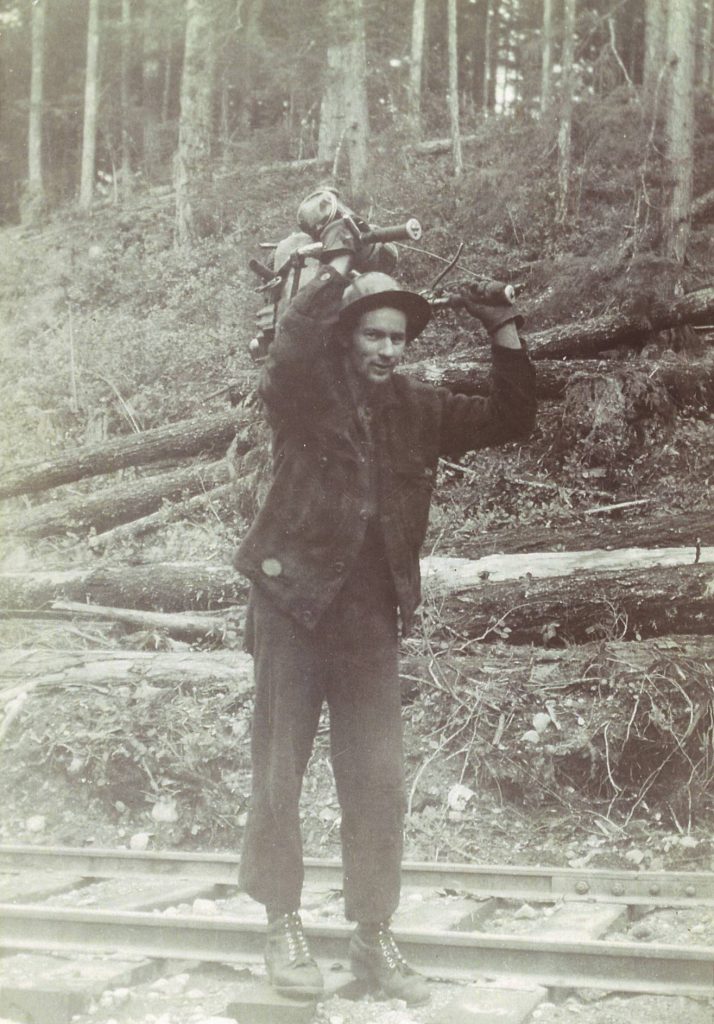

This, Virginia told me, was Violet’s husband, Walter. A five-by-seven photo shows him, again on a railway track, with a large and heavy chainsaw on his shoulder—and a wide brimmed hardhat on his head.

The news accounts of his accident stated that he wasn’t wearing the hardhat when he was hit by a falling limb, probably because he was eating his lunch at the time.

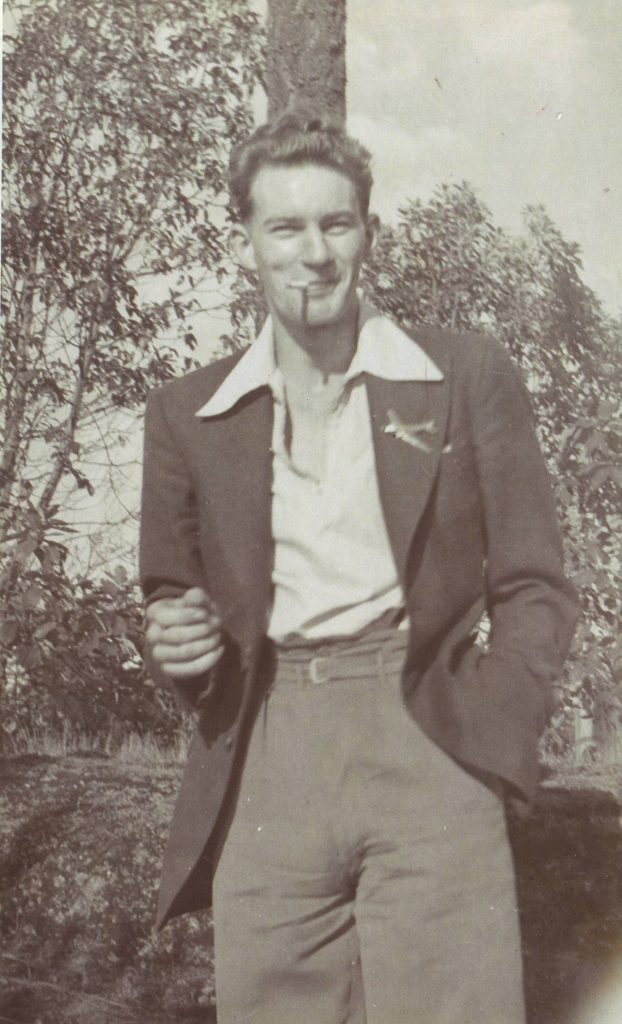

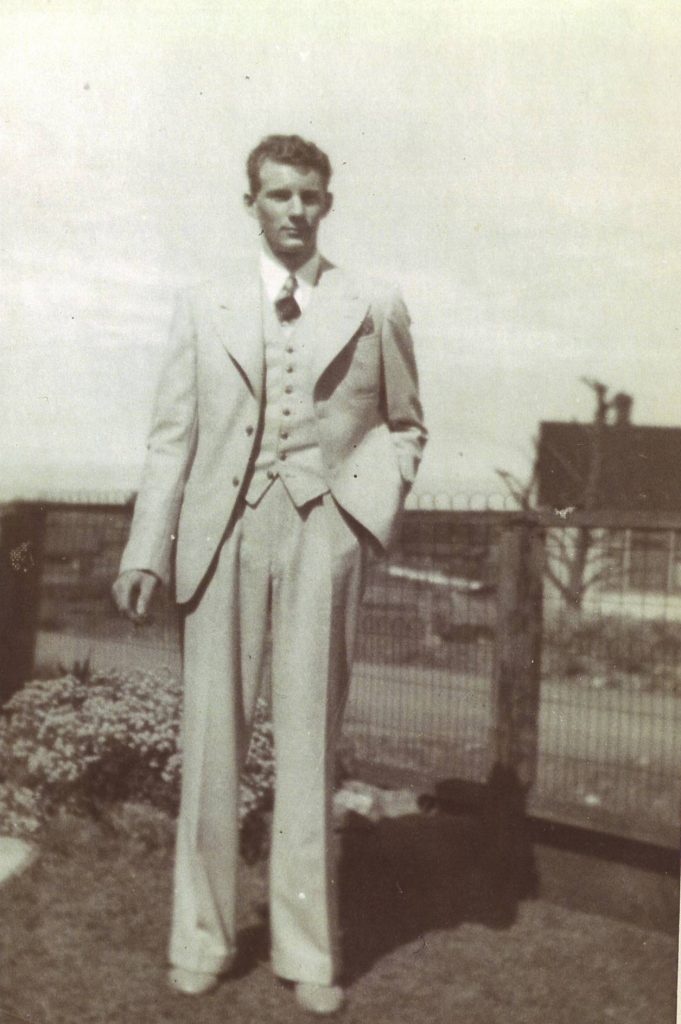

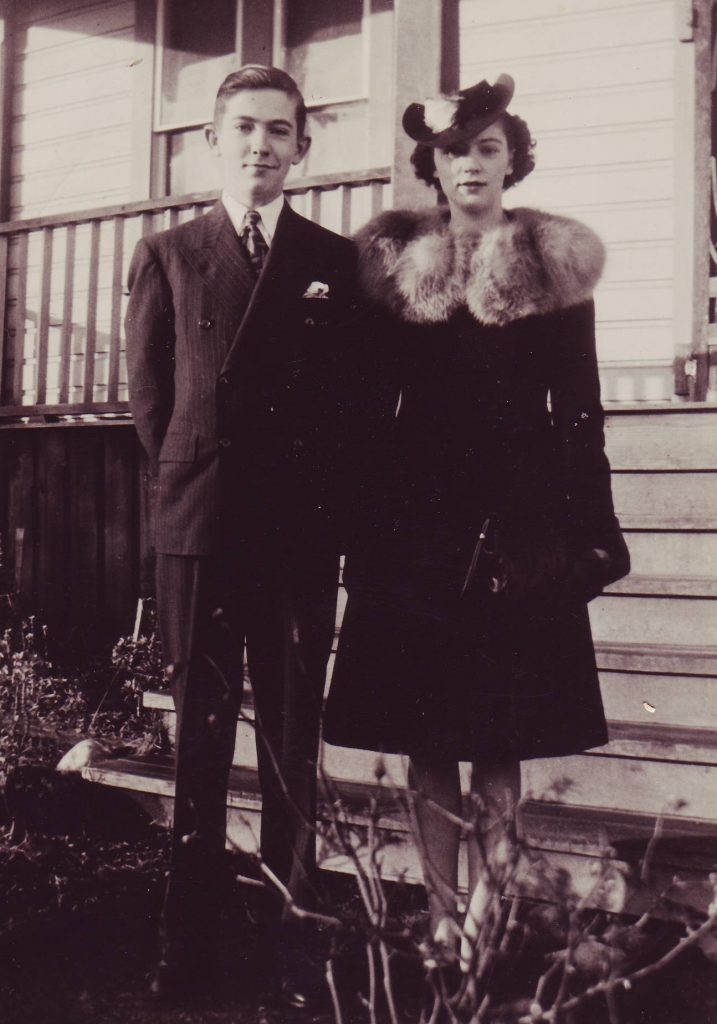

There’s also the dapper, six-foot Walter in suit with a carnation in his lapel beside a very 1940s attired Violet, another of him in white suit and tie, and looking like a Hollywood leading man. There’s a shot of him on their wedding day and yet another of Violet still wearing her corsage as they’re about to leave on their honeymoon.

They were a handsome couple.

Tom Teer’s mother, Vicki, who was born two years after Walter was killed, says other family members remembered Walter as being “nice looking, a nice dresser,” shy, gentle, an avid outdoorsman and a member of the local militia.

She believes that he, like his brothers Tom and Edward, left school early to go to work to help family finances. Both his and Violet’s family were from the same Northumberland community in the Old Country and Mrs. Teer thought it likely they met through the family network in Nanaimo.

She didn’t meet Violet until her grandmother’s funeral in 1974 and remembers her as being Walter’s alter-image—“very tall, good shape, and a little on the shy side, too”. Mrs. Teer next saw Violet when she was in her 80s in a care facility in Nanaimo, and quite infirm. She’d managed to surround herself in her small room with almost everything she held dear in this world.

Unfortunately, Mrs. Teer was dealing with her husband’s illness and her mother’s impending death and she couldn’t make allowance for Violet’s obvious wish to connect with her.

Although Violet never remarried, it’s known that she had a years-long relationship with an older man whom she cared for in his final years. She left no children.

As it happened, I took possession of all of Violet’s private archives. Virginia Jones had agreed that they should remain on the Island and I’d offered to pass the photos on to the Nanaimo Historical Society.

Because Walter was killed while working in the Lake Cowichan area, it was agreed that his framed photo and one of his short-waist faller’s shirts (one of several still hanging in Virginia’s bedroom closet) would go to the Cowichan Valley Museum and Archives.

Some time later, while dining with Tom and Cerys Teer, I showed them one of Violet’s albums of old Nanaimo photos. Tom noticed a name, Mrs. V. Hogg, written on the back of a hospital menu. Yes, I said, Violet Hogg.

Tom and mother Vicki suddenly leaned forward. “Why, that’s my Great Uncle Walter’s wife, Violet,” he said.

With the exception of the photo now in the Duncan museum, Violet’s treasures are in the safekeeping of Walter’s great nephew Tom, who spent much of a winter organizing, identifying and mounting the hundreds of photos which range from century-old professionally posed studio prints to fading 1960s Polaroid snapshots.

One, on top of the first box they opened, was of Vicki Teer in her graduation gown.

Such, as we know it, is a thumbnail sketch of the young faller named Walter Hogg who was killed on the job in 1943. Thanks to great nephew Tom Teer he’s one of the fallen forest workers who are now remembered on a Commemorative Brick in Lake Cowichan’s Forest Workers Memorial Park.

The Commemorative Bricks in downtown Lake Cowichan are a way of giving them deserved recognition year-round, not just on April 28’s Workers Day of Mourning.

I love human interest stories such as this as they bring you close to a young couple like so many other young couples whether it be in yesteryear or in todays world. I have come to know them through your story and their pictures and you actually feel the pain of poor Violet in losing her husband to such a tragic accident and like a lot of women of that day she never married again. Instead she hung on to her past by living with what remained of her dear departed husband. Thanks

Hi, Brian. The fact that his work shirts were still hanging in her closet when she died says it all! Violet’s and Walter’s is a true love story and tragedy.

And when you think of the thousands of other men who have been killed on the job, their lives, their hopes–and those of their families–cut short, it’s pretty sobering.

I could have written this post with broad strokes by telling about fatal forestry accidents in the multiple. But I think it has far more poignancy when narrowed down to a single young couple who’d been childhood sweethearts…

That said, should you ever visit the Forest Workers Memorial Park in Lake Cowichan, check out the other brown bricks. Everyone of them recalls a logger, like Walter Hogg, who had a wife and children and who were/are dearly missed.

This is one of the true joys of writing about history for me, by the way–the opportunity to honour all the Walter Hoggs of our province’s past. Cheers, TW