RMS Queen Elizabeth: WW2 Victoria’s best-kept ‘secret’

The Royal Mail Service Ship Queen Elizabeth was so huge she could be seen from Port Angeles–but no one ‘knew,’ early in 1942, that the world’s largest troopship was in the Esquimalt dry dock!

For 30 years I’d wanted to write this story but didn’t get around to it for lack of photographs. A need graciously filled by Chronicles reader Allan Scott whose grandfather, Allan Craig, was superintendent of the Esquimalt graving dock at the time.

The saga of the wartime dry-docking of the Royal Mail Steamship Queen Elizabeth, then the largest passenger liner in the world, and an unanticipated draftee into wartime service as a troopship, is all but forgotten today.

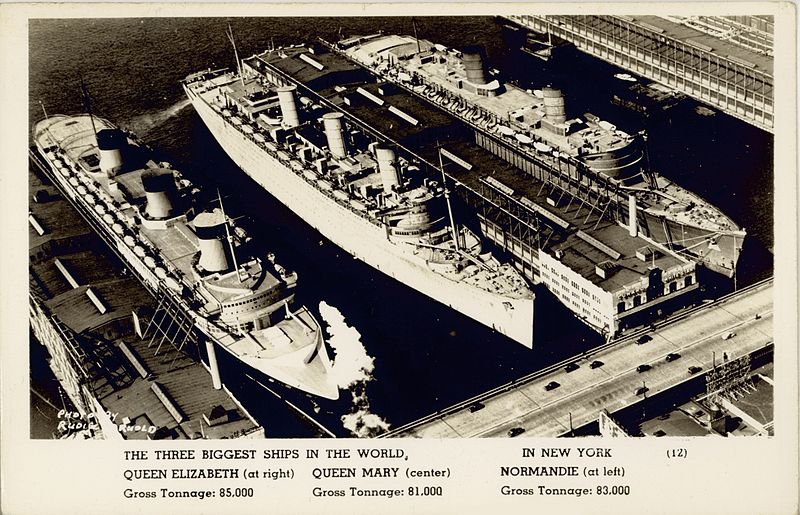

Built for the Cunard-White Star Line, at 84,000 tonnes she was even larger than her elder sister, RMS Queen Mary, and intended for passenger and royal mail service (hence the RMS) between Southampton and New York City. But war would delay her completion for six years and she’d cut her teeth, not as a palatial liner, but as a stripped-down and grim grey troop carrier.

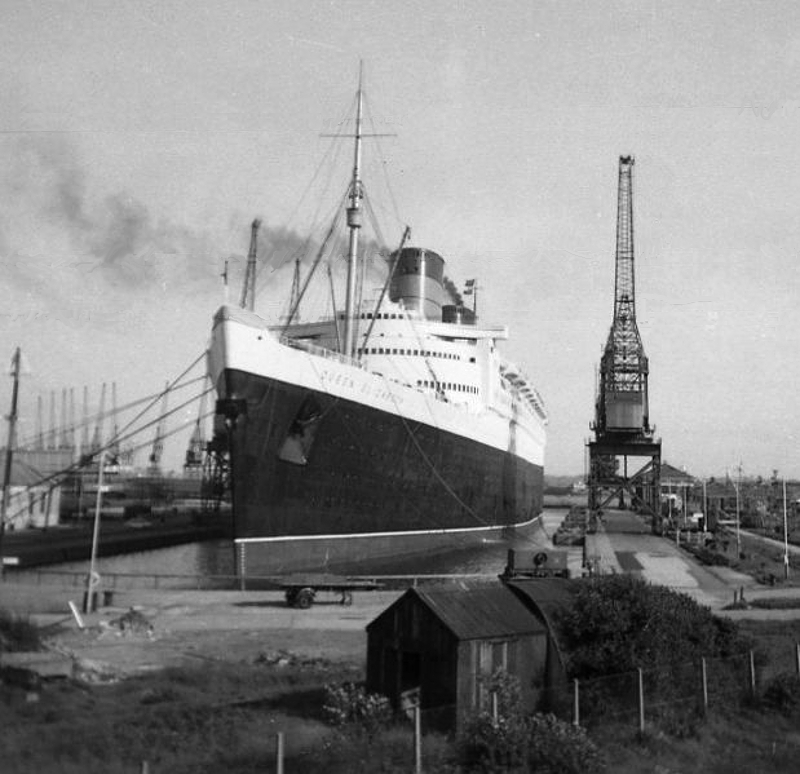

Not until the return of peacetime would Elizabeth get to strut across the Atlantic in the traditional Cunard livery of black hull, white superstructure and massive red funnels banded with black.

So speedy were the Elizabeth and Mary that they could sail without naval escorts–no sluggish Atlantic convoys for these royal ladies.

Elizabeth’s remarkable career began Sept. 27, 1938, with her launching by her royal namesake, Her Majesty Queen Elizabeth (mother of the present Queen Elizabeth II). As this was at the height of the Munich crisis, His Majesty King George VI couldn’t attend the great event, and HRH told the crowds of workers and guests attending the launch, “The King has asked me to assure you of the deep regret he feels at finding himself compelled at the last moment to cancel his journey to Clydebank…

“This ceremony, to which many thousands have looked forward [to] so eagerly, must now take place in circumstances far different from those for which they had hoped. I have, however, a message for you from the King. He bids the people of this country to be of good cheer, in spite of the dark clouds hanging over them, and, indeed, over the whole world…”

Also present that historic day were Princesses Elizabeth and Margaret, Lord Aberconway, chairman of the Clydebank shipyard, John Brown & Co., and the Cunard Co. chairman, Sir Percy Bates, Bart.

Because of the immensity of the job of her outfitting, the Second World War found Elizabeth still tied to her builders’ dock, a sitting duck for German bombers.

Worse, she was tying up dockyard space and shipwrights, both vital to the war effort. As she had to be moved out of immediate danger, it was decided to outfit her to the point that she could make it across the Atlantic to New York Harbour (the U.S. was neutral), there to join the berthed Queen Mary.

As the German U-boats that all but controlled the Atlantic would have made every effort to sink the world’s largest ship, if only for the propaganda value, and because it was impossible to make such a voyage in complete secrecy, it was decided to launch what would become one of the great deceptions of the war.

This would be the first of two in which Elizabeth would participate, the second being her ‘secret’ visit to Esquimalt, two years later.

It was announced that she’d be moved to Southampton for dry-docking. To complete the ruse, her 500-man crew was asked to sign ‘coast-wise’ articles, the Southampton dry-dock was informed of her impending arrival, she took on board a Southampton pilot and hotel rooms were booked in that city. Not even Capt. J.C. Townley knew of her real destination.

Her only wartime ‘armaments’ consisted of her battleship-grey paint and an anti-magnetic mine de-gaussing device that had consumed 30,000 feet of cable. There was no time for work-up trials short of testing her steering gear and compasses. On Feb. 27, 1940, Cunard White Star Ltd., in a complete break with precedent, had to accept delivery from her shipbuilders ‘as is.’

It’s a testimonial to the British workmanship of the day that, even in war time, she more than fulfilled all hopes and expectations.

Immediately before sailing, her crew was informed that she’d be making an ocean voyage and the few that declined to serve were held incommunicado until she was well underway. Finally, early March 2nd, after being fuelled by naval vessels, a sombre grey Queen Elizabeth ghosted down the Clyde and pointed her nose seaward.

She was on her own in the deadly Atlantic, without arms, without a naval escort, with only her secret departure and her speed, as yet unproven, to protect her. As it happened, the voyage went without incident and it’s recorded that much of the world was astonished by her turning up, publicly unannounced, in New York Harbour, five days later.

So began Queen Elizabeth’s wartime career as a troopship: Five years, five months, 18 days, half a million miles! It’s one of the most remarkable nautical careers of all time.

* * * * *

Straight from her builders, unfinished, untried, and across the Atlantic Ocean in five days to the safety of New York Harbour–not bad for the world’s largest liner, RMS Queen Elizabeth. Not bad for the British Admiralty either, which had successfully misled the world as to her real destination. That was in February 1940. Two years later, she’d turn up, ‘secretly,’ in the government graving dock at Esquimalt. Therein lies our tale…

This being pre-Pearl Harbour, she was dispatched from New York to Singapore (one of the few world ports with dry-docking facilities big enough to accommodate her) for completion, then it was on to Sydney for conversion to a troopship. Speedy enough, as was her sister, Queen Mary, to carry thousands of servicemen at a time without a naval escort, Elizabeth’s interior was fitted out with multiple and enormous kitchen facilities, sleeping accommodation (nothing like that which future paying passengers would enjoy) and a hospital.

On April 9, 1941, she cleared Sydney with 5600 Australian and New Zealand troops, bound for Suez, then, with Mary, she carried troops and reinforcements to and from the Middle East. This was demanding work. But the growing neeed to increase her passenger accommodations presented another challenge: Japan had entered the war.

Hence the decision, again determined by the need of facilities large enough to handle her, to dry-dock her in Esquimalt.

She arrived on February 25, 1942. At 233 feet above the waterline–that’s 20-stories high, she was taller than any building in downtown Victoria and could be seen from Port Angeles!

To put this is personal context, I remember viewing the Sedco-135 as it was being built at Victoria Machinery Depot in the 1970s from atop Mount Douglas in Saanich. The huge oil rig overshadowed everything along Victoria’s waterfront and was visible from almost any angle for miles and miles. It would have been even more so for Queen Elizabeth in 1942. All of which makes the fact that her presence in the provincial capital a ‘top secret’ almost laughable.

As one historian put it, “Thousands of Victorians had seen the grey silhouette of the massive passenger liner cruising, ghost-like, in Juan de Fuca Strait and come to anchor in the broad expanse of Royal Roads.”

Some secret.

Hundreds then converged on Skinner’s (Constance) Cove to watch as her 1031-foot bulk was eased into the 1150-foot dry-dock. It took two tries. Youbou’s Allan Scott knows the story as his grandfather, Allan Craig, was the graving dock superintendent: “On the first attempt…she came in a bit too fast, knocking over several chocks in the process. The ship had to be pulled back [to try] again the next day at high tide.

“There was approximately two feet of water under the ship’s keel and just inches to spare on each side. This very tight fit created a pressure wave off the bow, spilling water over the top like a miniature tsunami[!]

“In one of the photos you will see a gangway entering the ship. The dockyard personnel had to cut a hole in the ship’s side so personnel could enter without utilizing the crane bucket all the time.”

The father of his friend, Allan Brown, Jr., now in his ‘80s, was the docking master and assistant superintendent of Yarrows Shipyard. His had been the tricky job of easing Elizabeth into the dry-dock.

Around the clock, for 12 days and nights, thousands of shipyard workers, including high school students drafted for the purpose, and military personnel enlarged her troop carrying capacity to 15,000 passengers.

Twelve days and nights that she sat, helpless, unable even to use her speed to outrun any kind of attack, had the enemy had the means to strike her in Esquimalt.

For the duration of the war and almost 40 voyages, Queen Elizabeth delivered her troops wherever needed, virtually without incident–other than the time, off the Irish coast, a U-boat lined her up in its sights. Almost incredibly, for all her gargantuan size, all four torpedoes missed. Considering the number of troops she usually carried, her loss would have been the worst in maritime history.

By the time of her eventual release from military service in March 1946, she’d transported more than 800,000 service personnel, sailed just under 500,000 miles and visited every continent but Antarctica.

Finally ‘returned’ to the trans-Atlantic passenger service for which she was intended, Elizabeth was retired in 1969. Today, Queen Mary is a spectacular tourist attraction in San Diego. But Elizabeth, after a brief and ill-starred attempt to do the same in Port Everglades, Florida, was sold to a Hong Kong billionaire for conversion to a university for the World Campus Afloat program, as the Seawise University.

Alas, near completion of a 5 million-pound conversion, she caught fire on Jan. 9, 1972 and became a total loss. It’s fortunate that thousands of great photos were taken of this great lady, from her building to her wartime trooping days to her peacetime return to glory as a passenger liner. In particular, those photos taken of her ‘secret’ visit to the Esquimalt graving dock early in 1942.

10 Comments

Trackbacks/Pingbacks

- T.W. PATERSON – BRITISH COLUMBIA’S PIERRE BERTON | richardhughes.ca - […] RMS Queen Elizabeth: WW2 Victoria’s best-kept ‘secret’ […]

great story

Who knew, eh, T2? Hope you’re bushwhacking now that it’s spring.

Wow truly an incredible story.

Thank you, Angela.

Hi there…I’m the great-granddaughter of A.J. Daniels, Yarrows’ Dock Supt. until the late 1940s. We heard stories in the family about the QE under refit here and his role in the docking and refit. All his records were turned over to the Esquimalt Archives. I’m also a volunteer with the Vic High Archives and do the Vic High Alumni newsletter and I”m writing up an article about one of the ‘Secret Sixty’, the Vic High students recruited to work on the QE when she was here, specifically to clean out the boilers. Can I use one of the photos from your article to go with my story in our September e-newsletter? Thanks!

My apologies,Linda, I just saw this! Too late, I’m sure. The photos are all available online. Again my apologies for not responding promptly.

My Grandfather, George Gordon, was a joiner working at Yarrows’ at the time. He worked on the beautiful lady!

Right on! My father was a petty officer in the RCN and served for a time as a sentry at the entrance to the Drydock. Got into trouble when he refused to let a senior officer thorugh wihtout a pass!

My late father was one of the tug boat captains that put her in the drydock the second time.He took me down to see her from as close as he could

She must have been quite a sight for you as a child, eh? My father was in the navy at the time and at one pont was assigned as a sentry during her stay.